Is this the Archetypal Wicked Stepmother of English History?

Exploring Queen Elfrida’s Infamous Reputation

Hello, I’m Holly and I write about the untold tales of medieval lives. Subscribe for free to enjoy regular articles from me, including book reviews, historical discussions, and monthly roundups of what’s been great in the history/archaeology world. Or, even better, become a paid member to unlock ALL of my content, including all my historical fiction writing (flash fiction, short stories, miniseries and a serialised novel).

I wonder who you would consider to be the archetypal wicked stepmother of history?

A quick Google search throws up the possibility that the literary trope has its origins in the life of Livia Drusilla, the first Roman empress and second wife of Emperor Caesar Augustus. According to the discussion I read, Livia already had a son when she married Augustus, who himself had two sons from a previous marriage. Soon, however, both of Augustus’ presumed heirs wound up dead. There are no prizes for guessing who was at the centre of accusations of foul play.

In more recent literary history, the Brothers Grimm wove a tale of a wicked stepmother into their Hansel and Gretel, a story whose more gruesome edges have been softened over the years to delight young children with a tale of sugar and sweets.

And many of us will, of course, remember watching Cinderella’s wicked stepmother boss her about in Disney’s 1950 animated adaptation.

Today, however, I would like to transport you back over a millennium (though several hundred years after Livia’s life), to a woman most famous for murdering her stepson in order to place her own son on England’s throne. A wicked stepmother par excellence, you could say.

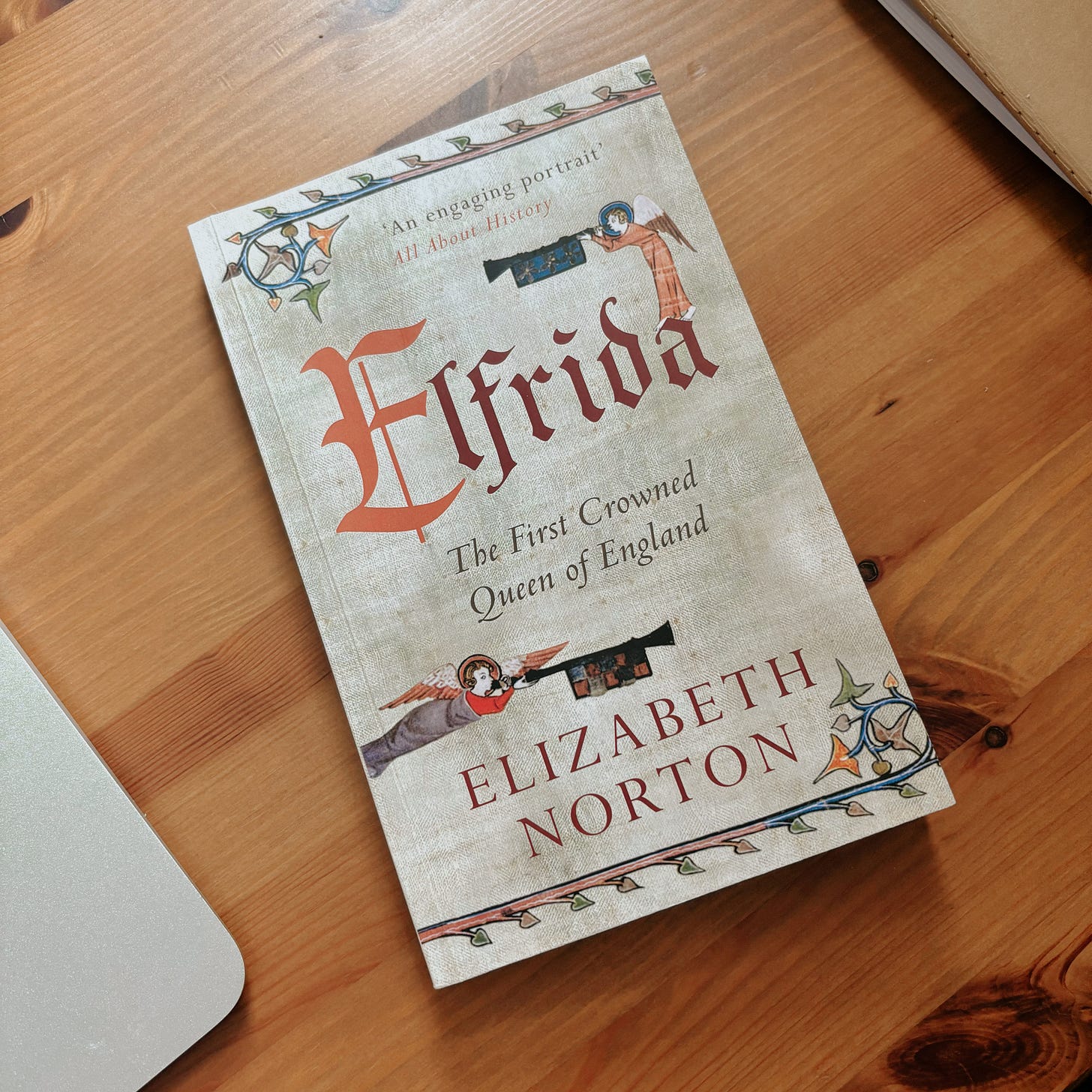

Elfrida: The First Crowned Queen of England, by Elizabeth Norton, was published in 2013, but it was not until almost a decade later that I picked it up while perusing the shelves of an unfamiliar bookstore. I was delighted, finally, to find a book that privileged the story of one woman in Anglo-Saxon England, rather than one that gifted her merely a chapter or a few pages at best. It is one of my biggest frustrations with the publishing industry that more books like this are not commissioned on a regular basis.1

This review follows on from that published in July focusing on Dark Queens by Shelley Puhak. Both books question the way that medieval women’s lives and reputations have been manipulated over time, and not often for the better. They show that medieval history doesn’t just have to be about kings and battles, and that the people who lived then were just as real as you and me.2

Who was Elfrida?

‘English history has produced many great and memorable queens, some with less than wholesome reputations. None can be said to have a reputation as black as the very first woman to be crowned as queen of all England: the archetypal wicked stepmother, Queen Elfrida.’3

Elfrida, or Ælfthryth as she would have called herself, was born in the mid-940s to a noble family. Her father, Ordgar, was a thegn, part of the second order of highly-stratified Anglo-Saxon society yet close enough to the king to be called to witness his charters. He was immensely wealthy, allegedly owning ‘land in every settlement from Exeter in Devon to Frome in Somerset, a distance of over 70 miles’.4

In 964, Elfrida married King Edgar, whom she had likely met years earlier during her first marriage. Edgar had also been married before, twice, but with Elfrida he made a significant change: she was the first of his wives to be called, and crowned, queen. Despite this, their marriage was deeply opposed by church and state, and they had ‘something of an uphill battle to establish her as queen rather than just the king’s wife’.5

She is, perhaps, most famous for an event that would take place in 978, following the death of her husband. For anyone unfamiliar with the story of her stepson Edward the Martyr’s murder, I won’t spoil it here. Needless to say, she and her son were the immediate beneficiaries of the heir presumptive’s death, and it didn’t take long for fingers to begin pointing in her direction.

‘All of the accounts of the murder of Edward the Martyr from the mid-eleventh century place the blame for the planning of the murder on Elfrida herself. In these accounts, she is portrayed as the archetypal wicked stepmother, ambitious for her own child at the expense of her stepson.’6

Why should I read this book about Elfrida?

What is unique about Elizabeth Norton’s book is that she looks at the broad sweep of Elfrida’s life, from start to finish. In other words, Norton doesn’t just focus on the disaster in 978 as the only point of interest for those wanting to learn more about this queen. She includes chapters on Elfrida’s role in religious reform, for example, as well as commentary on her and Edgar’s imperial ambitions, including that coronation ceremony in Bath in 973. In this way, she shows Elfrida as a rounded, whole person, rather than simply a murdering stepmother.

Yes, of course Norton devotes a lot of pages to the murder and its aftermath: it was, after all, perhaps the defining moment of Elfrida’s life, and has been subject to a lot of scrutiny in the millennium following the young ætheling’s death. What Norton does with the subject, however, is interrogate the evidence, including later accounts, to ascertain whether there is any justification for the accusations sent Elfrida’s way.

She provides the balance and nuance that we must always, as students of the past, be striving for.

Similar articles you might enjoy:

Though, of course, as an academic historian and archaeologist I completely understand the issue presented by the availability of sources, I do still think we could be doing better to write high-quality biographies of medieval women. This is something that

does so well here on Substack!Ok, so admittedly both of these books are about queens. BUT! Hear me out. Though they were not ‘normal’ people in the phrase’s common usage, their social position means that their lives and reputations have been maligned far more than those of women whose stories were never written down. It is just as important, therefore, that we uncover their true experiences, as women, in order to relate to them and see the connections between past and present. So often they have been written out of history, and yet we find time and again that they stood alongside kings at the centre of politics.

Elizabeth Norton (2013). Elfrida: The First Crowned Queen of England. Amberley Books: Stroud, p.6.

Ibid, p.7.

Ibid, p.61.

Ibid, p.145.

Love this 🥰🥰🥰

@John Paul Davis and @Polly thank you for sharing 🙌