💬 Does it matter that women's stories were told by men?

Unpicking a problem inherent to medieval women's history

Dear Medieval Musers,

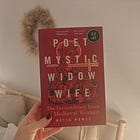

A few weeks ago I shared a review of Hetta Howes’ magnificent book, Poet Mystic, Widow, Wife: Extraordinary Lives of Medieval Women (2024), a history of medieval womanhood through the writings of four medieval female writers: Marie de France, Julian of Norwich, Christine de Pizan, and Margery Kempe.

In the review, I shared that I was most impressed by Howes’ determination to place the spotlight on women’s words, prioritising their words to tell their stories.

‘All four of them were writers, a rare profession for women at the time, and this presents us with a unique opportunity. By reading their words and listening to their voices, we can start to piece together a picture of what life was like for medieval women.’1

As an early medievalist researching the role of women in the dynamic social and political changes of 6th- and 7th-century Europe, I am faced daily with the reality that almost no women of this period have left their own words behind for us to read. As the vast majority of written evidence was produced by men, so much of women’s history for this period derives from men’s words.

And as a result, our picture of medieval womanhood is, largely, mediated by men: what they thought about women; how they thought women thought; and what they thought important to write down about women.

It’s led me to ask the question: how different would our picture of the medieval world be if we had a body of written evidence produced by women, comparable to that which survives from their male contemporaries?

In another recent essay, I shared the story of Bertha, a 6th-century Frankish princess married off to Æthelbert of Kent, at the time of his marriage son of the ruler of a kingdom in no way comparable to the Merovingian dynasty he’d become entwined with.

Gregory of Tours (HF: IV.26) describes her simply as ‘a daughter [of Charibert, king of Paris] who afterwards married a husband in Kent,’ not even giving her name.

Bede (HE: I.25) describes her as ‘a Christian wife of the Frankish royal family, whose name was Bertha’ whom Æthelberht ‘had received her from her parents on the condition that she should be allowed to practise her faith and religion unhindered, with a bishop named Liudhard whom they had provided for her to support her faith’. Bede later mentions Bertha to deplore her complete lack of effort (or so he asserts) to convert her husband to Christianity, and then to mention her place of burial.

From these descriptions, we would be forgiven for assuming that Bertha had nothing to do with the immense political and cultural changes that swept across eastern Britain following Æthelberht’s conversion under the mission sent by Pope Gregory the Great in A.D. 597.

But if we look to the history of her home kingdom and the roles played by her female ancestors and relatives, the very women she had grown up amongst or at the very least hearing stories of, some of whom she shared DNA with, we begin to build a more nuanced picture of female political involvement than Bede would have use believe.

Women such as Clothild, Queen of the Franks (d. A.D. 544), who ‘did not cease to tell the king [Clovis, her husband] that he should worship God and desert the vain idols he honoured’, who implored him ‘to believe in almighty God, Father, Son, and Holy Ghost’, engaging this most powerful of men on multiple occasions in theological debate akin to the kindd ascribed by Bede only to the men of his narrative.2

Women such as Radegund, Queen of the Franks and Abbess of Poitiers (ca. A.D. 525-587) who very self-consciously and publicly played the role of holy Christian wife in the face of her husband’s polygamy, in such a way as to enter the knowledge of those writing accounts of her life, such as Venantius Fortunatus.

Don’t hear me wrong!

These accounts of Frankish queens were still written by men (with the exception of possible collaboration between Radegund and Venantius Fortunatus on his verse account, ‘The Thuringian War’).3

But what they indicate, to me at least, is that the very one-dimensional picture given by Bede of women’s history in the early Anglo-Saxon era might not be giving a truly representative account of women’s actions during this period.

Which leads us back to the question posed at the start of this essay, a more fundamental one to the study of women’s history, and my question for you.

Does it matter that so much of women’s history, particularly for the early medieval period, is contained within men’s words? How different would our picture of the medieval world be if we had comparable volumes of accounts from men and women?

Would you join me in the comments with your perspectives on this question?

I’d be so grateful to hear what you think - in agreement, disagreement, confusion, or otherwise.

If you enjoyed this essay, then you might also enjoy these 👇

Hetta Howes (2024). Poet, Mystic, Widow, Wife. London: Bloomsbury Continuum. pp.xii-xiii.

The Life of Saint Chrothildis, §3 & §2. tr. Jo Ann McNamara (1992). p.41.

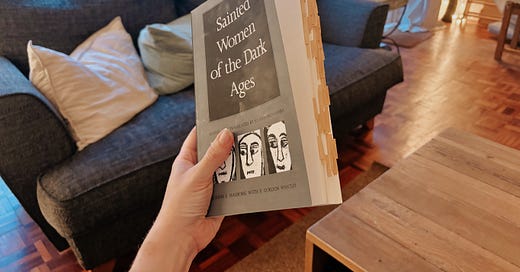

Jo Ann McNamara, ed. (1992). Sainted Women of the Dark Ages. Durham and London: Duke University Press. P.61.

It matters in that it happened, but it's a filter that can't be removed. It's common across Antiquity as well, but I get the sense, reading in the older period, that for the most part, it hides the voices of the women more effectively. When women in Late Antiquity and the early Medieval period are quoted (or "quoted"), the writer has an intent to express their point of view, whereas with older writers, women either were invisible or, more generally, the target of social or political criticism.

Male writers may be unreliable narrators of what the women thought, but they weren't producing in-depth psychological studies of what Clovis was thinking either. It was enough for them (and must be for us) that Clovis was sticking by his Frankish gods out of custom, and Clothild was literately debating his theology. It reveals more about her and her education, status and viewpoint than it does about the King's. Looking at her, I learn that she was a highly educated, intelligent, and political postRomano-Germanic woman with a strong will. He comes off as faceless, a force of featureless resistance to her intent.

If we had a time machine (or a chronoscope) we could sort it all out, but unless some monastery (or the carbonized Pompeiian library) can yield rarer manuscripts from 500BC-AD1000, the evidence is gone (assuming it existed.)

Two observations which spring to mind immediately. It would of course be lovely to think that writings by women would paint a different picture - I would certainly like to think so - but I fear it wouldn't, for a few reasons.

1/ If women had been able to produce writings which survived (women of more than one 'class', that is) then this would presuppose a different society (a more equal one, I mean, in which women were allowed to express themselves more), in which case they'd tell a different story, not to mention that history would be a lot different (better too, no doubt). So there's a sort of logical consideration there.

2/ It may be the case that had certain women been able to write accounts which survive down to us, then we would have the same social-history questions for them and their accounts - namely, 'to what extent were they conditioned by the social mores and orthodox ideology of their time?'. To give a modern parallel - there were a lot of women who did not support the suffragettes, even worked against them. What if the only accounts we had of the suffrage movement was written by those sorts of Conservative-type women?

Perhaps what I'm suggesting here is we have to keep in mind the social background of the writer, male or female. Remember too that the male writers were just as conditioned by the society in which they lived. And they all have agenda-like intentions with their writing (propaganda, that is). Of course I would love to see a female writer with a sort of dissident agenda from that period, but the best we can hope for there would be someone today imagining such as a work of historical fiction (which I would love to read!).

Alas!