Men are great, but they're not the whole historical story: Bertha, Queen of Kent (c. A.D. 565 - ?601)

Rediscovering Medieval Women

In stories of the early medieval period, powerful women rarely get the limelight. They stand, rather, in the shadows of the men they lived alongside.

Time and again contemporary written sources sideline these women, transforming them into minor characters or bit-part players in the grand narratives of their husbands’ lives (or those of their brothers, sons, grandfathers, and so on).

And with an alarming lack of discernment and criticality, the male-dominated pictures presented by these sources have been perpetuated in historical narratives for the past 1,000+ years.

Many of these women, though, were powerful political players in their own right.

This essay launches a new series inspired by a question at a recent discussion panel held by

, in which , , and I talked about historical storytelling in a digital age.An excellent host, Cosi opened the conversation with this question:

Women’s history month is all about amplifying voices that have been overlooked. Is there a particular moment or figure from history that you personally think deserves more airtime?

I cheated, answering that it is the category of the women standing in the shadows of the historical narratives - those who played vital roles yet were excluded from the records - whose stories have a right to be told.

So, lovely readers, for the next few months I’ll be sharing the stories of some of these women from the very earliest days of early medieval England, hoping to resurrect their lives and characters from the ashes of unfavourable historiographical treatment, starting with my absolute history hero: Bertha, Queen of Kent.

Do make sure you’re subscribed to avoid missing out on later essays, covering queens, saints, and locally-significant women.

Who was Bertha?

Born in c. A.D. 565 to Charibert, king of Paris, and his wife Ingoberga, Bertha was a minor member of the Frankish ruling dynasty who married Æthelberht, king of Kent, probably in the 580s. Though marriage to a Frankish princess would likely have been considered political advancement for Æthelberht’s family, its unlikely that the feeling was mutual. When describing Bertha’s marriage, Gregory of Tours, a near-contemporary source, explains that her intended was simply ‘a husband in Kent’ (HF: IV.26), suggesting that no great political or economic benefit was expected of the match.

Much has been made of Bertha’s Christian faith, acknowledging the note in Bede’s Ecclesiastical History (written c. A.D. 731) that she be allowed to bring her bishop, Liudhard, with her to Kent and that she continued to worship Christ when queen (HE: I.26). Her family, however, had a much more complex relationship with Christianity than this picture might suggest. While her great-grandfather Clovis I famously converted to Christianity in A.D. 496, her father Charibert (d.567) was excommunicated and her grandfather Clothar I (d.561) was married to five women.

How has her life been overshadowed?

Though she can lay claim to being the first Christian queen of an Anglo-Saxon kingdom in England, she was given barely a mention in contemporary or near-contemporary written sources.

Gregory of Tours is so brief in his reference to Bertha that if you speed-read his History of the Franks, you’ll likely miss her.

‘King Charibert married Ingoberga, by whom he had a daughter who afterwards married a husband in Kent and was taken there.’ (Gregory of Tours, HF: IV.26)

So unimportant was Bertha to the overarching purpose of Gregory’s narrative that he doesn’t even give her name and describes her largely through her relationships with the men he was more interested in.

Bede, too, references her only in relation to the process by which her husband Æthelberht, king of Kent, converted to Christianity. She is, yet again, a woman made historically-significant thanks to the actions of the men around her.

‘Some knowledge about the Christian religion had already reached him [Æthelberht] because he had a Christian wife of the Frankish royal family, whose name was Bertha. He had received her from her parents on the condition that she should be allowed to practise her faith and religion unhindered, with a bishop named Liudhard whom they had provided for her to support her faith.’ (Bede, HE: I.25)

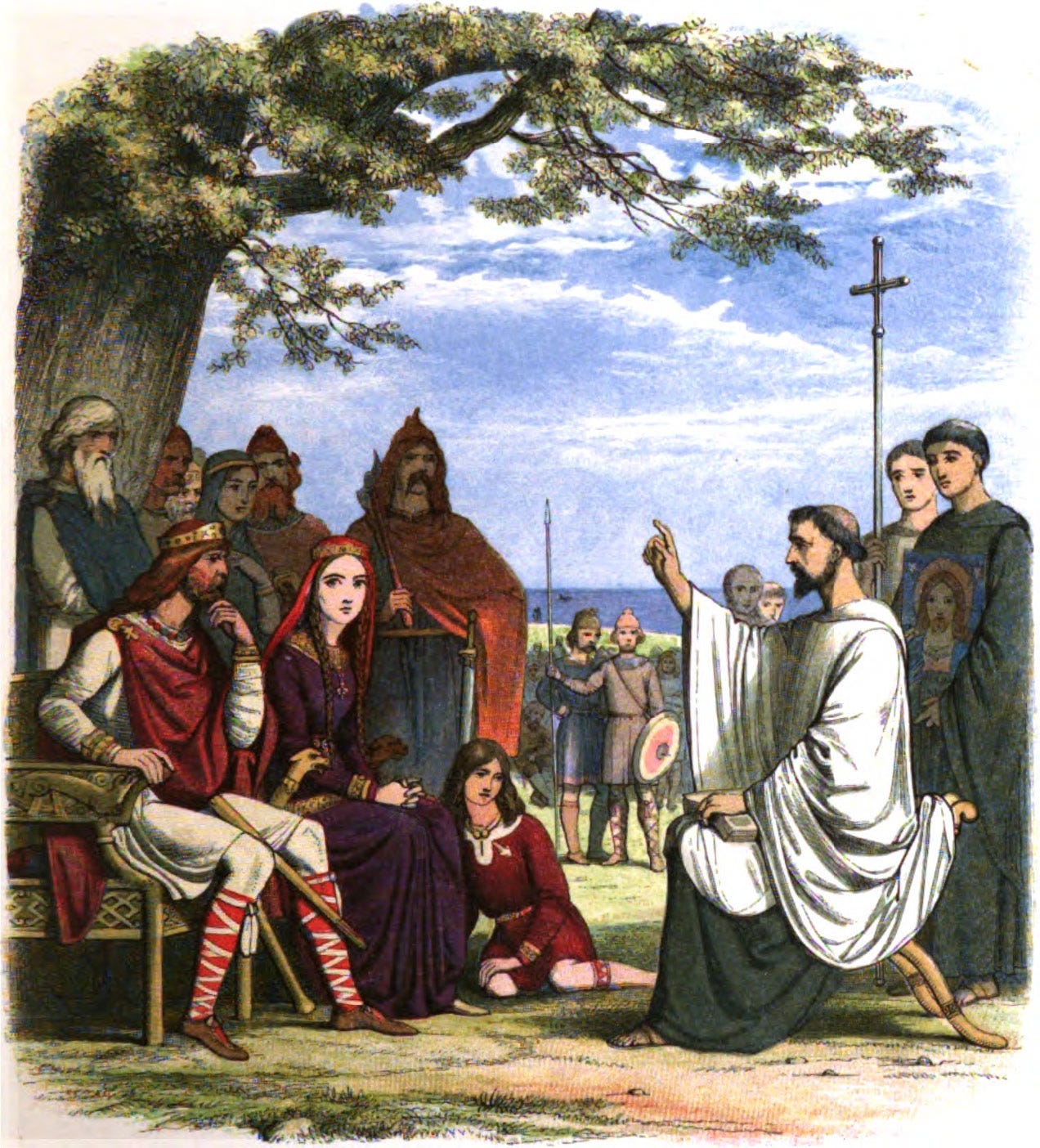

In his narrative, Bede places the credit for Æthelberht’s conversion squarely on the shoulders of the recently-arrived mission from Rome, headed by the monk Augustine. He goes to great lengths to describe the anguish with which Æthelberht wrestled over the question of whether to abandon the gods of his ancestors (I.25, 26) - but gives no role to his wife, despite acknowledging that some knowledge of Christianity had reached him through her.

Perhaps this is stepping beyond the remit of history and straying too much towards conjecture, but I find it very difficult to believe that Bertha was as irrelevant as Bede makes her out to have been. She had been married to Æthelberht for over 10 years, possibly closer to 20, by the time Augustine’s mission reached these shores, giving plenty of opportunities for them to have spoken about Christianity. Bertha’s family were bold enough to insist on a Christian presence in her marriage train; is it possible that she too was gutsy enough to talk theology with her husband?

Later writers, too, pick up Bede’s judgement of Bertha and keep her firmly in the shadows of her illustrious husband.

Sir Frank Stenton’s classic history, Anglo-Saxon England (first published 1943), lists Bertha in its index as ‘w. of K. Æthelberht of Kent’: here, too, she is important only as the spouse of a man. Stenton goes on to describe her as a passive individual, a pawn in the political machinations of the men around her (1971: 59). Though this goes further than Bede’s account suggests, Stenton argues that Bertha made ‘no attempt to explain her religion’ to Æthelberht, promoting instead the explanation that it was Augustine’s missionary efforts that led to the king’s conversion (1971: 105).

Though more recent scholarship has increasingly recognised Bede’s tendency to ignore non-Roman Christian influences (including the enormous impact of the Irish and British churches around the hinterlands of the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms), this seems to be slow to trickle into popular publishing, the avenue through which most modern readers learn about history. Marc Morris’ recent publication, The Anglo-Saxons (2021), while lively and engaging, repeats the Augustine-centric message of Bede’s account and, furthermore, mentions Bertha only as she relates to her husband.

There are some seeds of hope, however. Writing almost half a century after Stenton, James Campbell’s iconic work, The Anglo-Saxons, acknowledges that Bertha’s marriage was ‘the first link in a chain of events which was to lead to the conversion of England’ (1991: 44).

Can we tempt her to step any further out of the shadows?

How can we tell her story when the written sources just aren’t there?

It is a sad truth that many powerful, influential medieval women will remain largely lost to history due to the simple fact that their contemporaries didn’t deem them important enough to waste ink and parchment on. Particularly for Bertha, who lived at a time when writing was so new that only a handful of written sources survive, we’re unlikely ever to be able to write a thorough account of her life - barring the miraculous discovery of some previously-unknown text.

We can, however, build a picture of the world she lived in and use this to inform our judgements of what she may have been like. Recent work on exogamy, the practise of sending women abroad for marriage, is illuminating the networks for exchange of ideas these relationships formed. By studying that movement of people similar to Bertha, we can start to reconstruct her own milieu: the education she might have received, individuals she might have connected with, places she might have visited. New understanding about female landholding in sixth-century Francia is significant here too: by exploring the roles that women had in local politics, we might be able to hypothesise about Bertha’s day-to-day life in running the Kentish royal household.

Let’s work hard to bring these women out of their husbands’ shadows - and allow their stories to shine on their own merit.

I’d love to know how you’d have answered Cosi’s question, the one that sparked this new series of essays on overshadowed women:

Women’s history month is all about amplifying voices that have been overlooked. Is there a particular moment or figure from history that you personally think deserves more airtime?

If you’re happy to, let me know in the comments which moment or figure from history you’d like to see given the spotlight.

I don't have a woman per se (unless it is Gerda Lerner!!!...so guess I do) but erasing women from history… This is why Gerda learner had to write a whole separate book, entitled “creation of Feminine consciousness” after she wrote “creation of patriarchy”. In fact, that was actually her first book she wanted to write, but couldn’t until she wrote “creation of patriarchy”. Why? Because she couldn’t find consistent women’s history throughout the ages. She proved that women had to start over from scratch constantly to recreate their history in order to see themselves in it, and thus as an active participant in the world. One has to ask why would erasing women from history be necessary for the patriarchy? Answering that question might help you wake up. Next week on my YouTube channel, I will be releasing a video about how history is made and it’s vital that we understand IT IS made and not just coming out of the thin air. It’s more about probability than facts as we are seen in real time witht his DEI erasure thang.

Another woman I am "rewriting into history" (because I feel this is what we will have to do to spark our imagination about women in HERstory back alive) via my fictional book is Mary Magdalene. She is going to have a deep back story centering around the story of Inannana and the women who carried the Genetrix ("the Ancestress" Creation STory in my book) in secret until the time of Mary Magdalene. In my book, she is the Christ -- teaching Jesus how to "love the neighborh, sinner, prostitute and tax collector" that biblical historical scholars still are not sure where he got that message from (why from a WOMAN but of course) ;-)!

I absolutely want to join this conversation. Some years ago I came across 2 sentences that mentioned Isabelle d'Angouleme, the 2nd wife of King John. She lived some 600 years after Berta, and was widely reviled in the chronicles. I have written an historical novel trying to unearth her life by digging into details that are knowable about 1200 England and France. She lived in turbulent times - wars and power struggles with the pope culminating in the Magna Carta. If John was a besotted with her as the chronicles suggest, she surely had some influence.

Sharon Bennett Connolly, Fellow of the Royal Historical Society, blurbed the novel as "a stunning recreation..." which made me feel like I had succeeded. Of course, In creating her world, I had all the info I wanted about the men, but had to extrapolate it for her and the women surrounding her. If you're interested, the novel is Behold the Bird in Flight, coming in June but you can preorder now. (I hope I've not embarrassed myself by this bit of promotion...).

I'll be following this thread closely. Thanks for starting it!