Crafting Beauty: Making Books in the Middle Ages

Review | The Medieval Scriptorium by Sara J. Charles (2024)

Hello there! I’m currently studying for a PhD in Archaeology at Oxford, researching the role of women in the social and political developments of 6th- and 7th-century England and France. With a worldwide readership of over 4,400 PLUS featuring regularly in Substack’s top 100 fastest-growing history publications, I share medieval history as you rarely hear it. I combine written and archaeological evidence to share the experiences of overshadowed individuals, ask challenging questions of dominant interpretations, and recommend books and writers doing a wonderful job of unearthing the past. My top 3 posts of all time have been a review of Rebecca Stott’s Dark Earth, biography of Æthelthryth of the Northumbrians (the queen who wouldn’t sleep with her husband), and my guide to Oxford’s top medieval moments.

Crafting Beauty: Making Books in the Middle Ages

Review | The Medieval Scriptorium by Sara J. Charles (2024)

‘It is so intrinsically human to express ourselves through writing, whether venting frustration or jotting down a silly doodle - and it is an incredible connection to the past. That scribe, hundreds and hundreds of years ago, touched that parchment with their hands, worked over it, breathed over it, felt happy/sad/cross/content/hungry/silly/bored or inspired - all the normal emotions we might feel during our working day - and sometimes they let us into their world by expressing that on the parchment. That tangible connection with the past, touching the manuscript that the scribe has touched - and goodness knows how many people in between - leaving invisible (and sometimes visible) fingerprints that link us inextricably with our past selves, is a uniquely human experience.’

Sara J. Charles (2024)

There are indeed few things that connect us more tangibly with the people of the past than the objects they handled themselves. When we pick up something produced in a world so vastly different to our own, it is as if the object acts as some sort of connective tissue, binding us with those who made it, used it, and eventually lost or deposited it. Because they, too, touched that very same material, despite everything else that separates us.

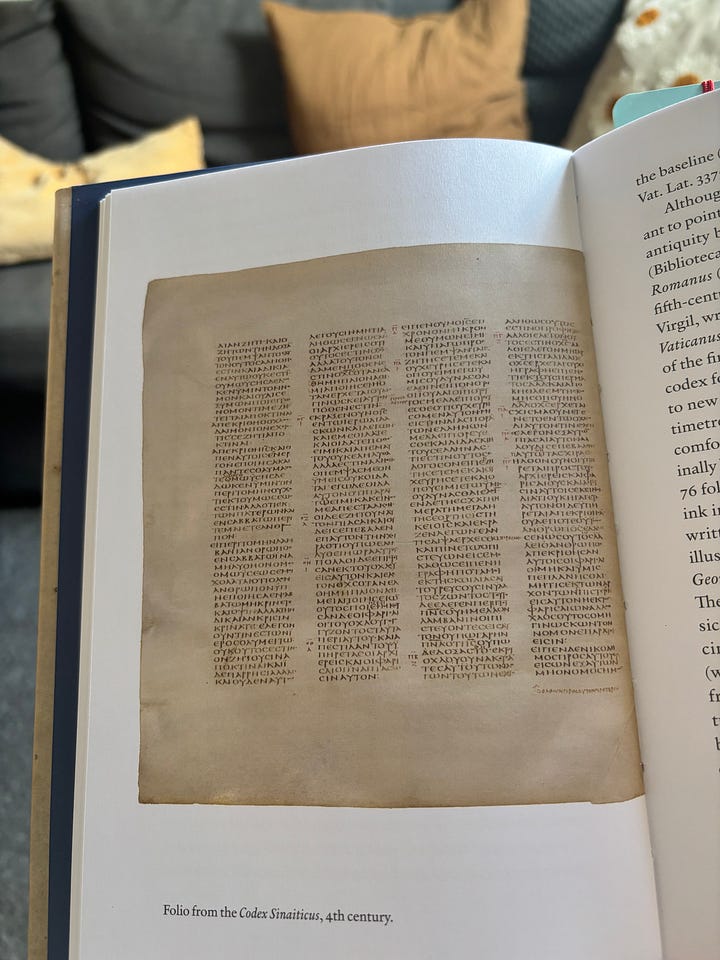

Aside from material culture, the corpus of mundane and spectacular objects that survive from history, perhaps the most accessible route into the past is through its books. For over 2,000 years, humans have used writing and imagery to record what was important to them and though only a fraction of what was originally produced survives today, it is a beautiful record of artistry and craftsmanship.

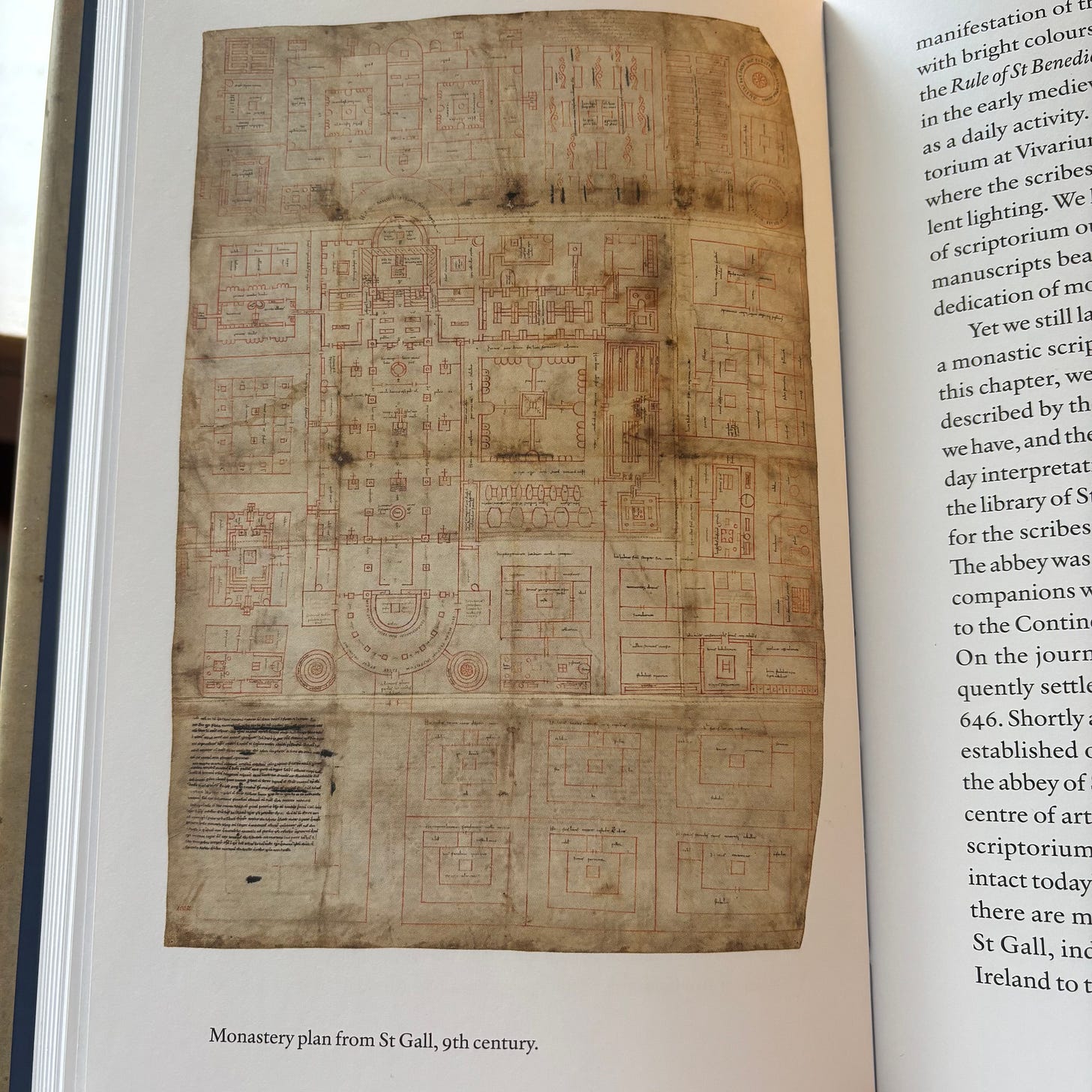

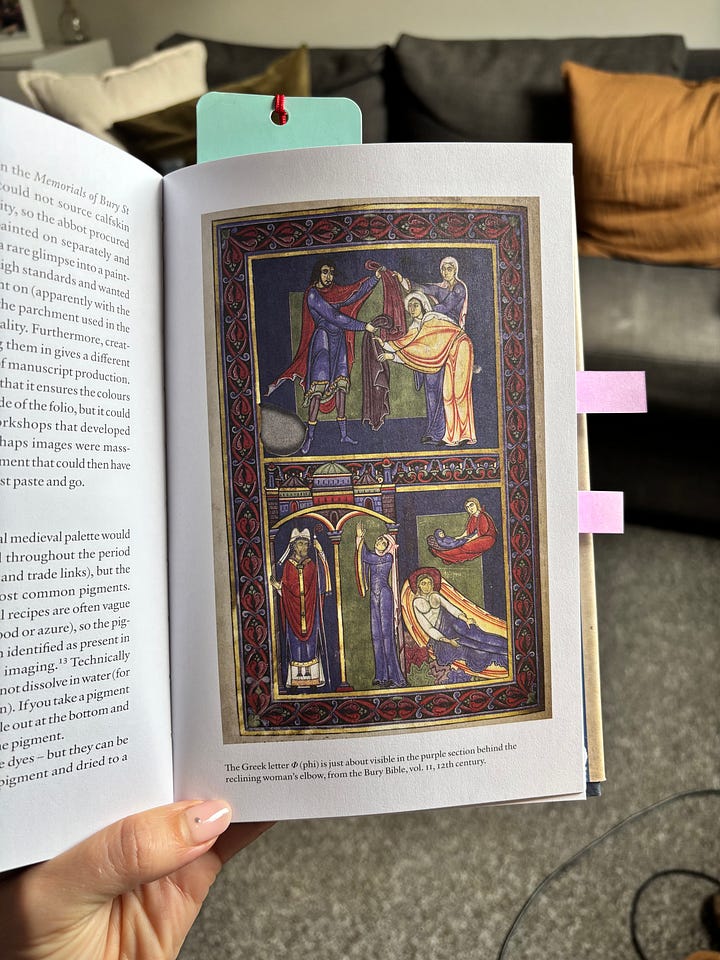

Sara J. Charles’s recent book, The Medieval Scriptorium: Making Books in the Middle Ages (2024) is a beautiful journey through the process of medieval bookmaking from its origins in the ancient world to its demise with the advent of the printing press. She includes narrative chapters telling the story of the rise and fall of the manuscript in addition to more practical chapters on the place of writing, the materials for writing, and the skilled work of illumination.

Each chapter starts with a fictional vignette related to its theme that helps the reader to locate themselves in the world they are about to learn about. This is, after all, a world much unlike our own. Though there is much that would be familiar about the human experience of those living up to 1,500 years ago, their physical world and daily routines were unaffected by the onset of the technological age that came with the Industrial Revolution in the West, including its intellectual changes. Charles’s vignettes help the reader to step out of our own world and become one with the protagonists of her story, preparing us for all we are about to learn.

‘Brother Ciarán! The Lord does not reward idleness!’ the senior monk reprimanded the new scribe, who had been staring dreamily into space. ‘Sorry, Brother Eoghan,’ said Ciarán humbly. He shifted uncomfortably on his wooden bench, laid his quill down carefully next to his parchment and flexed his stiff hand. He sighed heavily and leant back on the cool stone wall, looking out at the unfamiliar Frankish monastery. He had only arrived at Luxeuil monastery a few days ago, having been sent from his hometown of Bangor Abbey after Abbot Columbán requested Abbot Comgall send his finest scribes to join him in Luxeuil.’1

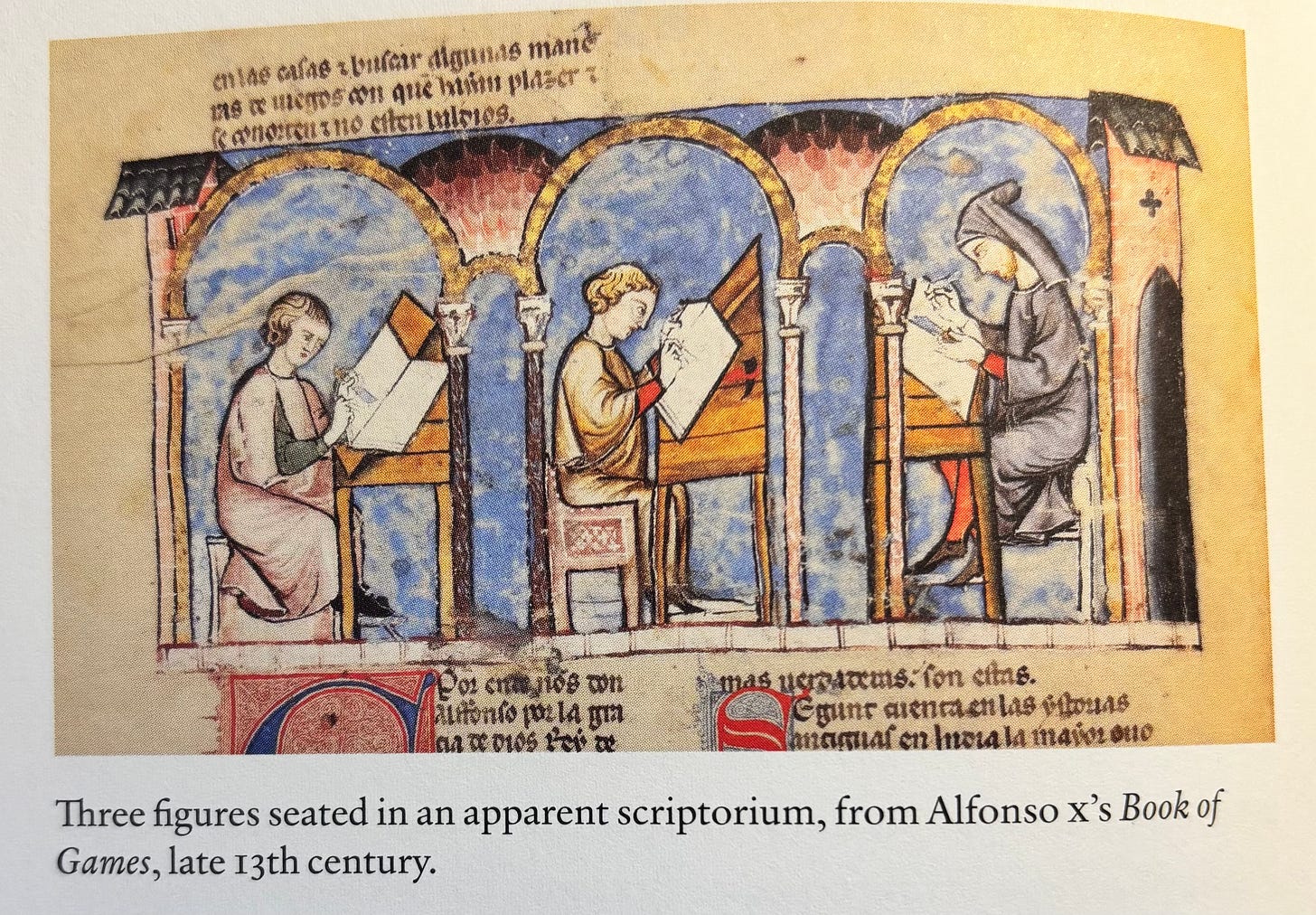

One thing that surprised me is that though the concept of ‘the medieval scriptorium’ feels familiar and concrete, ‘we still lack the archaeological and pictorial evidence of a monastic scriptorium - the actual room and its contents.’2 We probably imagine a square or rectangular room, bright with large windows and high ceilings, and rows upon rows of monks or nuns hunched over small desks laden with parchment, ink, and manuscripts to copy from. Perhaps there’s a particularly strict overseer looking for mistakes, as in the vignette above. According to Charles, however, it’s ‘time to put the traditional image of a scriptorium … to one side and create a new one.’3

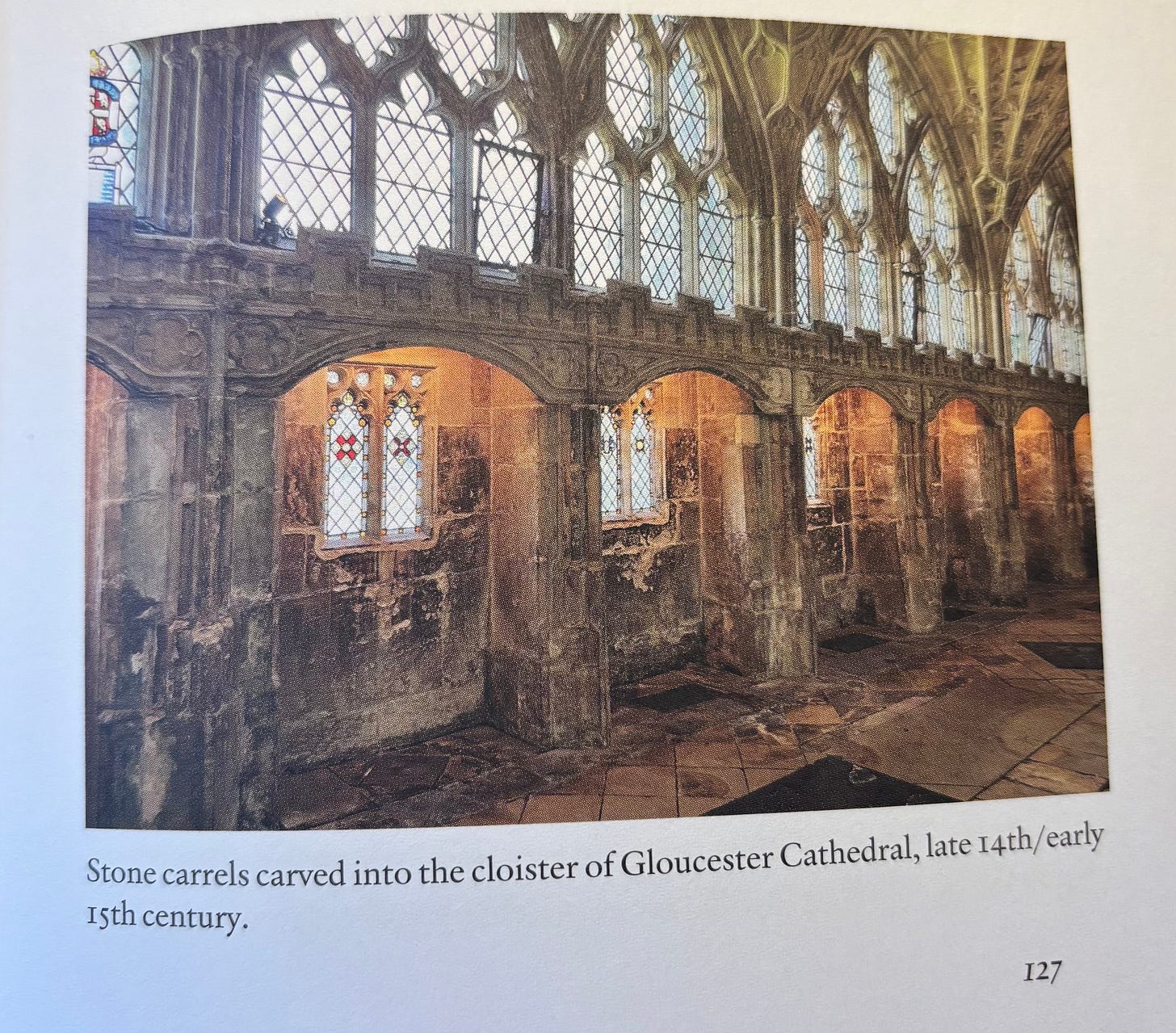

There was so much more variety! For those in what we might call a ‘classic’ monastery, it seems that book production took place in the cloister. Some scribes were lucky enough to have individual ‘carrels’, small study rooms or cells set into the walls of the cloister that provided enough light and quiet to produce intricate, careful reproductions of well-known texts. The Liber ordinis Sancti Victoris Parisiensis, a French source written in the early 12th century, says this:

‘Fixed places for this work [writing] are to be arranged apart from the community, but within the cloister, where the writers can concentrate more quietly on their work without disturbance or noise. Those sitting and working there should carefully stay silent and not wander about idly. No one should go to them except the Abbot, Prior, Sub-Prior and Librarian etc.’4

It wasn’t always the dreamy quiet workspace we might imagine, however, as this marginal scribble from a monk at Ramsey Abbey in Huntingdon reveals:

‘As we sit here in tempest, rain, snow and sun, No writing or reading in cloister is done.’5

Existing in a world before central heating, the medieval monastery could be bitterly cold and draughty in the winter months, despite best efforts to keep warm with fires and hearty stews. They were much more at the mercy of the elements than we are today, so it is possible that they had to down tools when their fingers were at risk of seizing up due to cold, in order to ensure that the manuscripts they produced were of the finest quality.

‘Now, numbed by the winter cold, I turn to other pursuits; and, weary with toil, resolve to end my present book here. When the warmth of sweet spring returns I will relate in the following books everything that I have only briefly touched upon, or omitted altogether.’6

This marginalia also reveals the innately relatable, human side of the scribes who produced these manuscripts. Although I enjoy seeing marginal scribbles in the books that I borrow from libraries, 21st-century readers are not really supposed to make their mark upon books that do not belong to them. And it would be tempting to think that medieval scribes, producing faithful reproductions of texts placed before them, would have the same duty of care. Charles dives into the theme of textual alterations in detail, but there are also shorter, more casual notes around the edges that reveal the character of our forebears - and there is much that is relatable about them.

There is, first, the musings of a scribe working on the manuscript now known as Laon, Bibliothèque municipale, MS 26, a copy of a commentary on the psalms by Cassiodorus dating from the 9th century, who says, ‘I feel quite dull to-day. I don’t know what is wrong with me.’7 Later on, there is an Ogham inscription, an early medieval script used in Ireland consisting of a series of strokes across a central line, in which the scribe says he has been ‘killed by ale’ (i.e., he has a hangover).8 Then there is the whinging of a scribe working on an early 9th-century manuscript on the law-codes of the Burgundians, who says

‘Those who don’t know how to write think it easy. O how hard it is to write! It strains the eyes, breaks the kidneys, tires all of your limbs at the same time. Three fingers do the writing, but the whole body labours. Just as a sailor wishes to arrive at his home port, so does the scribe long for the last verse.’9

Hard work it may have been, but what they produced was spectacular. From the early rows of regular script unbroken by word breaks through to the illuminated manuscripts more familiar to students of medieval Europe, these manuscripts stand as a testimony to the artistry and craft of medieval men and women, who were just as talented as any individual today.

If you are interested in learning more about the work of book production in medieval Europe, I would highly recommend this book by Sara J. Charles. With images set throughout the text and a delightfully heavy quality to the paper, it is a fitting tribute to the work both surviving and lost of countless men and women throughout history, to all of whom we owe our understanding of the past. For without their efforts, through the trials of cold weather and hangovers, we would have no written record of that beautiful, richly textured world we love to study.

Publication Details

Publisher: Reaktion Books

Publication date: 19 Aug. 2024

Language: English

Print length: 344 pages

ISBN-10: 1789149169

ISBN-13: 978-1789149166

This review of Sara J. Charles’s The Medieval Scriptorium: Making Books in the Middle Ages (2024) is part of a series of essays sharing books that are working hard to overturn the dominant narratives in medieval history publishing. Frustrated by my own struggles when wandering the aisles of many a bookstore, I want to show that there are books out there that explore more than just kings and battles, opening up more interesting conversations than the same biographies and political histories that we’ve been reading for centuries.

Last month we looked at Emily Murdoch Perkins’s Regina: The Queens Who Could Have Been, which you can read more about HERE, and next month I’ll be sharing my thoughts on two new releases, Behold the Bird in Flight by

(published just this week) and The Graces: The Extraordinary Untold Lives of Women at the Restoration Court by (due to be published on 17th July 2025). Make sure to subscribe now to have that review land straight into your email inbox!If you enjoyed this review, then you might also enjoy…

Charles (2024: 57).

Ibid, p.115.

Ibid, p.130.

Quoted in Charles (2024: 125).

Ibid, p128.

Ibid, p.129.

Ibid, p.141.

Ibid, p.142.

Ibid, p.140.

I'm torn about buying this book - it would simply provide a few lines in the current work-in-progress and maybe a setting description - but it sounds fascinating in its own right, beyond research. I'll give it some thought!

I’m about to do a course with Sara so I am very interested to see your review. Thank you for sharing it.