'A fantastic, feminist dance through history'

Review | 'Regina: The Queens Who Could Have Been' by Emily Murdoch Perkins (2024)

Hello there! I’m currently studying for a PhD in Archaeology at Oxford, researching the role of women in the social and political developments of 6th- and 7th-century England and France. With a worldwide readership of over 4,400 PLUS featuring regularly in Substack’s top 100 fastest-growing history publications, I share medieval history as you rarely hear it. I combine written and archaeological evidence to share the experiences of overshadowed individuals, ask challenging questions of dominant interpretations, and recommend books and writers doing a wonderful job of unearthing the past. My top 3 posts of all time have been a review of Rebecca Stott’s Dark Earth, biography of Æthelthryth of the Northumbrians (the queen who wouldn’t sleep with her husband), and my guide to Oxford’s top medieval moments.

'A fantastic, feminist dance through history'

Review | 'Regina: The Queens Who Could Have Been' by Emily Murdoch Perkins (2024)

‘Many historians, including myself, have been trained to ignore the temptation of the ‘what if’ game. What if this particular person had died of the plague before they… sparked a war? Married an enemy? Invaded a neighbour?’

Emily Murdoch Perkins (2024)

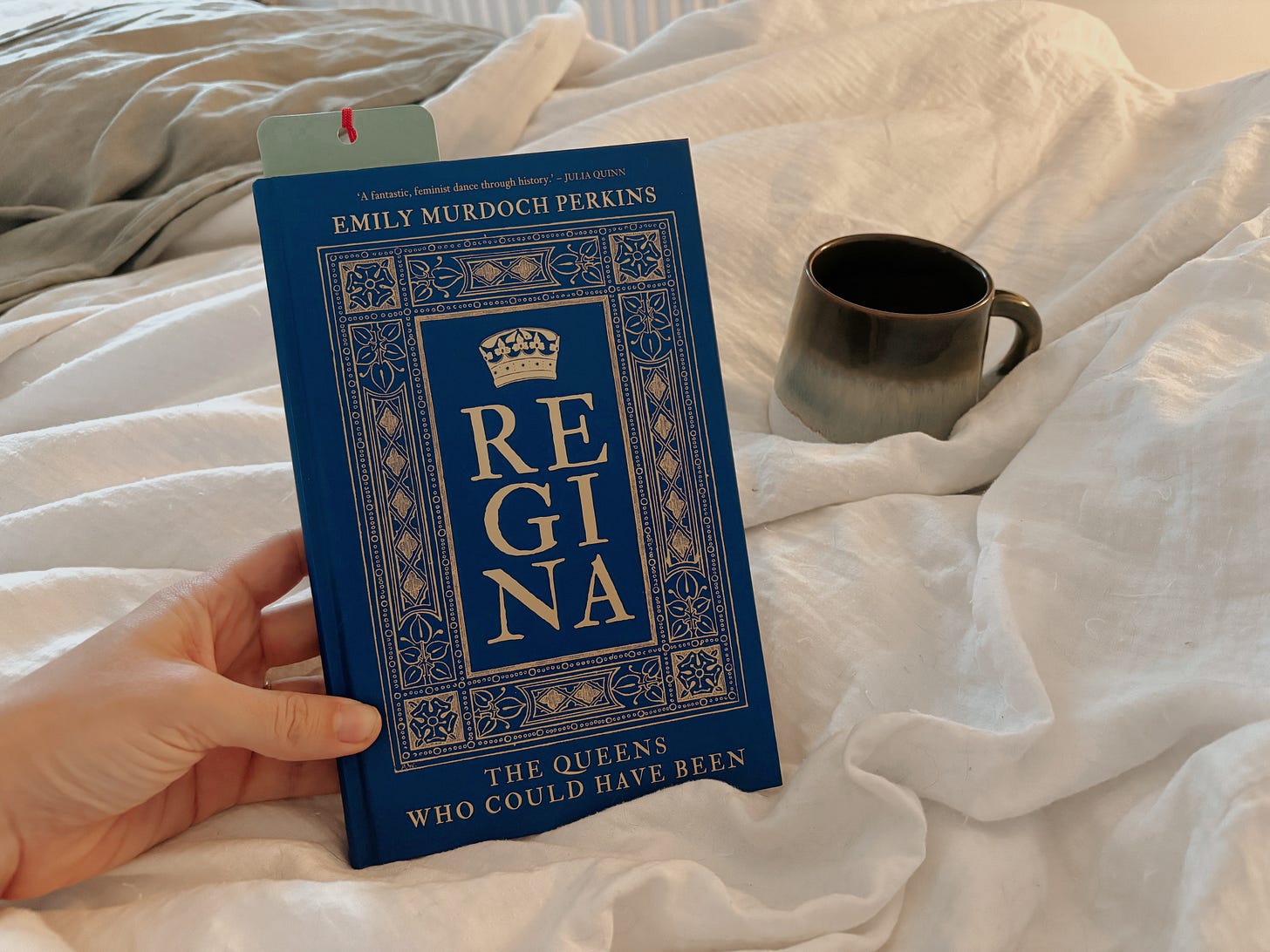

I recently read Emily Murdoch Perkins’s thought-provoking book, Regina: The Queens Who Could Have Been (2024). It’s a collection of biographies of royal daughters, with a consideration of how they might have ruled had women been allowed to succeed their fathers.

‘My favourite question, the one I return to again and again, unable to relinquish the exciting academic and creative challenge is this: What if … it were daughters and not sons who inherited the throne?’ (Perkins 2024: 7)

Perkins traces through a broad sweep of English history, starting with what she calls ‘The Edith Queens’ (c.870-?), moving through ‘The Nordic Queens’ (990-c.1093) and ‘The Norman Queens’ (?-1182), into the familiar realms of ‘The Plantagenet Queens’ (1102-1275), ‘The Edward Queens’ (1269-1382) and ‘The Rose Queens’ (1392-1503), before turning finally to more recent history with ‘The Renaissance Queens’ (1489-1662), ‘The George Queens’ (1687-1828), and ‘The Modern Queens’ (1840-today). She ends with a chapter on ‘The Queens Who Were’ (1516-2022), sharing ‘the bits you don’t hear’ about Mary I, Elizabeth I, [William and] Mary, Anne, Victoria, and Elizabeth II (Perkins 2024: 223).

With engaging storytelling and a lighthearted tone, Perkins overturns what she calls our ‘idea of daughters as dutiful, marital conveniences to build alliances, wearing long flowing dresses’ (Perkins 2024: 8). Instead, she reveals ‘political intriguers … abducted nuns who demanded divorces … [and] murderers’: royal daughters behaving a little differently to how we might expect (Perkins 2024: 8).

It’s a highly dynamic picture that emerges, of women who repeatedly took matters into their own hands, asserted their sense of self, and made their situation work for them. There are, of course, a handful of tragic tales: women who died young, and those subjected to harsh treatment either by their fathers or by their husbands.

‘This book will introduce you to women who could have been your monarchs … We’ll explore what it meant to be royal, why and how sons came to be valued higher than daughters, and just how England, then Britain, might have looked under royal matriarchy.’

Emily Murdoch Perkins (2024)

At its heart, though, is that ‘what if’ question: What if … it were daughters and not sons who inherited the throne?

Perkins is clear about the scope of her work:

‘The one thing I won’t be doing is the impossible: attempting to track the ‘new’ royal family line that could have been created if Æthelflæd [the first of her ‘queens who could have been’] had successfully passed her power to her daughter Ælfwynn … Instead, I’ll introduce the eldest daughters of English monarchs, and explore how their rule might have looked. Yes, it’s speculation. Yes, it’s intrigue. Yes, it can never be proven either way. But isn’t it enthralling?’ (Perkins 2024: 14).

What this looks like in practice is a series of biographies, each made up of two parts: a factual account of a royal daughter’s life, followed by a brief excursus exploring how she might have ruled, based on what’s been learnt from the sources about her.

'A fantastic, feminist dance through history' - JULIA QUINN

When preparing to write this review, I asked subscribers on Notes what they believe to be the enduring allure of the ‘what if’ questions. With diverse research interests and backgrounds, their responses were illuminating.

- : ‘I think “what ifs” are best approached carefully, as moments to emphasize agency. So the further “down the decision chain” you go the less useful they are. A big part of my dissertation was actually questioning why a certain choice made sense. In essence, applying a counterfactual lens to it. People make choices within informational, political, and cultural contexts, so good counterfactual history seeks to understand what other choices were available. Sometimes the answer is a person in the past made a choice because they simply had a personal reason! Where what ifs get frustrating for me is when they create perfectly coherent counter-narratives. It assumes a mechanistic view of human agency where choices can be “predicted” and applied over time.’

- : ‘I think the ‘what ifs’ are fascinating because such a small moment or decision can change so much for so many. Sometimes playing out the alternative scenario brings the conclusion that the progress or change was inevitable and that a different decision would have accelerated or slowed the change. The critical thinking around these what-ifs is important and can flush out people who may have played (or could have played) roles in these significant moments and change how we think about pivotal events.’

- : ‘We’re fascinated by ‘what if’s’ because history turns on individuals’ lives: their births, their decisions, their deaths. Considering alternatives helps us think about what could have been, and perhaps helps us see (sometimes) the randomness of it all, and sometimes the inevitability. Europe was in the middle of protestant reform in Henry VIII’s reign - was the switch in England inevitable, but with greater or lesser bloodshed? Political and social forces beyond the individual are also at work and every decision has to be seen in that context - but it still comes down to the individual action, which may be one weighed and considered, or one made from anger or love or revenge, all of which have consequences that echo down the ages. We judge those consequences based on our own political beliefs and values now; academic distance is a difficult thing to maintain.’

For me, ‘what if’ questions are so interesting because the alternatives in our own lives, what some call the butterfly effect, feel so close to our reality. What if I hadn’t sent that text? What if I hadn’t gone on that date? What if I’d chosen a different job? Life sometimes feels made up of chances taken and others lost, with consequences that could so easily have been different had we chosen a different path. Had historical people done just one thing differently, we might not be reading the stories we know today.

‘There were many women who could have, if the rules had been different, become queen. The eldest daughters who, but for a chance of fate, could not take the regnal crown. The queens who could have been.’

Emily Murdoch Perkins (2024)

I’ll admit, I wasn’t too sure when I started reading this book that I’d make it to the end. Drawn in by the beautiful cover and pleasant size of the book when I saw it in a local bookstore, I initially found Perkin’s upbeat tone a little too chipper. Long-time readers know, I am all about making history interesting and engaging, so it’s not that I think books should be dry and serious. What I do appreciate, though, is integrity, and I find sometimes that a more casual tone jars with that (for me).

I needn’t have worried.

By the time I’d read a few of the daughters’ biographies, I was hooked. There is, perhaps ironically, something about Perkins’s writing that drew me in and left me wanting more. I found myself reading a section a night (e.g., all of ‘The George Queens’, 30 pages covering Sophia Dorothea, Anne, Charlotte aka. ‘Royal’, and Charlotte) and within a couple of weeks I’d finished the book.

I loved it.

Publication Details

Publisher: The History Press

Publication date: 24 Oct. 2024

Language: English

Print length: 256 pages

ISBN-10: 1803995602

ISBN-13: 978-1803995601

This review of Emily Murdoch Perkins’s Regina: The Queens Who Could Have Been (2024) is part of a series of essays sharing books that are working hard to overturn the dominant narratives in medieval history publishing. Frustrated by my own struggles when wandering the aisles of many a bookstore, I want to show that there are books out there that explore more than just kings and battles, opening up more interesting conversations than the same biographies and political histories that we’ve been reading for centuries.

Last month we looked at Karen Brooks’ The Good Wife of Bath, which you can read more about HERE, and next month I’ll be sharing my thoughts on The Medieval Scriptorium by Sara J. Charles, the book subscribers chose as our next review in our exclusive subscriber chat. Make sure to subscribe now to have that review land straight into your email inbox!

Wonderful review. My TBR pile is going to topple soon...

I wrote about counterfactual history last year, and, while I find it often fascinating and enjoyable and entertaining, the most important quality in my view is that what-ifs remind us that nothing in history is inevitable, however we process events after the fact so that they seem to make sense.

https://theideaslab.substack.com/p/counter-factual-history-for-good