Many Dark Age historians loathe the term ‘Dark Ages’.

Why?

For so long, historians decried the lack of written sources for the period in England immediately following the withdrawal of Roman troops in c. A.D. 410 and before the arrival of the Christian mission headed up by Augustine in A.D. 597. It was, to their minds, historiographically ‘dark’: without the written sources, they claimed, little could be known about the people that populated this era.

The irony is that the so-called ‘Dark Ages’ are exceptionally archaeologically visible thanks to the practice of furnished burial which flourished during this time.

Prior to A.D. 597, the practices of cremation and inhumation (burial of a body) flourished in equal measure, with a little regional variation, and both were often placed in the ground with objects that represented who the individual had been in life and what they might need for their journey on in the afterlife.

With heavy use of glass and metal objects, much of this material survives to the present day - and, excitingly, new archaeological techniques are making it possible to identify the remains of more perishable materials such as fabrics, wood, and plants.

And so many of us who study the ‘Dark Ages’ would like, rather, to reframe it as something of a ‘Bright Age’: a culture who recorded their history and belief not on papyrus or parchment but rather through oral poetry, stone sculpture, landscape features, jewellery fashions, and so much more that communicates to us through archaeological rather than written material.

This essay is the product of a trip I made recently to the British Museum in London, one of my most favourite sites of historical interest. With so much there, it would be possible to spend a whole day wandering its many rooms and still be left with areas unseen.

I, however, always make a beeline for Room 41: Sutton Hoo and Europe A.D. 300-1000.

Call me obsessed, but I want to see the objects handled by the very people I study, feel that tangible connection with a culture long gone from these islands.

I have written a few of these ‘travel diaries’ before, such as for my trip to Beddgelert in North Wales (where I discussed the evidence of place-names) and for my trip to Conisbrough Castle in South Yorkshire, which claims to be the burial place of the Anglo-Saxon origin hero Hengest.

If you love travel diaries or early medieval sparkly history, do make sure you’re subscribed to avoid missing out on future posts!

Just a heads up: this essay contains a lot of images so some email providers may cut off the end. For the best experience, read it in the app: it’s free and easy to download at the link below.

Ok, so I had a spare hour in London and I knew exactly what I wanted to do.

The trip didn’t exactly start ideally, though. I turned up to the entrance of this iconic museum to be asked for my ticket. Ticket?! That’s new since I last visited. Thankfully, it’s still free to enter; they just like you to have booked in advance. As I hadn’t done this, though, I had to enter the museum through a back entrance. A bit weird, but I made it in eventually.

Then I discovered that many of the medieval galleries are currently closed. Disaster! Happily, though, the Sutton Hoo room was still open (though I had to enter that through a back entrance too; weird…).

And it is just as beautiful as I remembered from my last visit, another baking hot day (40+℃ on that occasion, 25℃ this time).

One of my all-time favourite artefacts greets you upon your entrance into the room.

The Desborough necklace, discovered in Northamptonshire, is typical of high-status female jewellery fashions in the mid-7th century. Consisting of twisted gold wire beads, gold-and-garnet cabochon pendants, and a central gold cross with garnet decoration, it was worn by a lady who had thoroughly eschewed the Germanic fashions of the previous century, choosing instead a necklace that drew parallels with contemporary Byzantine styles and even those of ancient Rome. She was no doubt a member of the aristocracy, perhaps even royalty. Sadly, though, her burial was discovered quite by chance by workers towards the end of the 19th century and thus incompletely recorded, so we have no way of knowing what else she was buried with.

Next we are treated to some of the older treasures, artefacts and assemblages from 5th- and 6th-century burials in England and continental Europe.

The objects deposited with this cremation are typical of a high-status 6th-century female. The large festoons of amber and glass beads that formed her necklace were added to across her life, signalling her international connections, and the ‘latchlifters’, curious key-shaped iron objects, signify her role overseeing the household.

Coloured glass vessels are a common find in 6th- and 7th-century burials, thought to represent either the individual’s feasting and hosting activities in life or the final meal enjoyed by mourners during their funeral service. The examples in the image above are from English burials, while those in the image below are (I believe) continental. Both demonstrate the advanced glass-working skills of early medieval craftspeople.

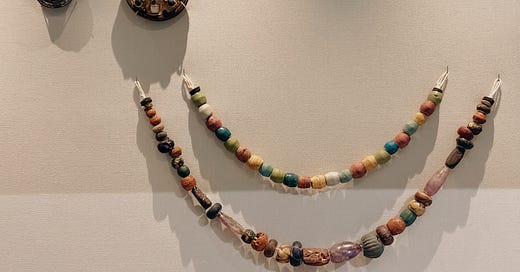

Female fashion gradually shifted during the 7th century, away from those large festoons of amber beads to more delicate ‘necklet’ types that incorporated exotic materials, such as the amethyst beads in the image below. These were likely strung across the chest, rather than worn as a necklace, and attached to the pairs of brooches pinned at the collarbone that held up dresses.

Many of these brooches and necklace pendants were made of gold, with delicate filigree work and inlaid garnets and shell, both exotic materials available only to the well-connected. They were a status symbol, yet became increasingly accessible to individuals across the social spectrum, sometimes appearing in graves with few other indicators of wealth.

There is also the Franks Casket, a box carved from whalebone bearing both Christian and Germanic imagery and bearing runic descriptions. It’s a real melting pot of cultures and ideas, symbolising the various traditions and societies that came together and interacted in England during this period.

The main character in this room, however, has to be the Sutton Hoo treasure. Excavated in 1939, the vast barrow burial contained an entire clinker-built ship laden with gold treasure, feasting vessels, fabrics, and so much more. Though no body was discovered due to the acidic nature of the soil (and many have argued that it is more likely an epitaph than a burial), this must have been the final resting place of a very powerful king, able to command the resources to build such an impressive monument and dispose of so much wealth without it affecting the security of his dynasty’s grip on power.

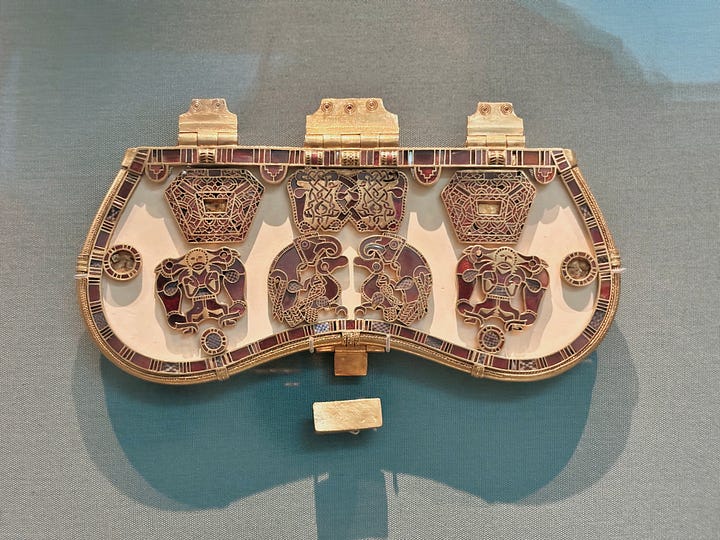

I didn’t photograph all elements of the burial assemblage, but rather picked out my favourite pieces: the famous helmet, modelled on Roman parade helmets and featuring scenes from mythical tales; the beautiful shoulder clasps, again designed on Roman military gear, with intricate gold-and-garnet cloisonné decoration; the ivory-inlaid purse lid; the highly-detailed great buckle.

To me, these items particularly symbolise the complete antithesis of the term ‘Dark Ages’. Yes, it is absolutely true that the period is historically ‘dark’ because of the lack of surviving written source material. But that doesn’t mean, as so many historians of the past have done, that we should discount it as inaccessible. These people recorded their history and their culture in their objects and we can learn a lot about them through the items they’ve left behind.

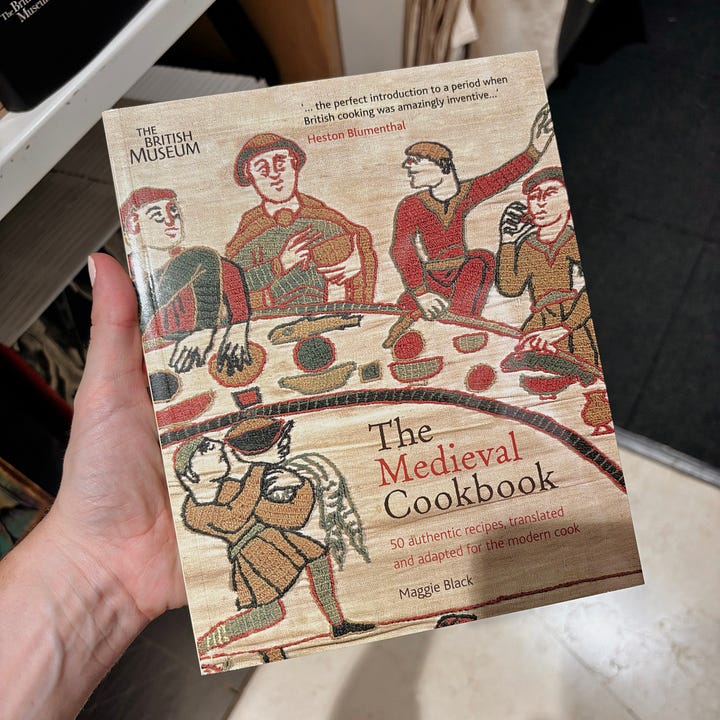

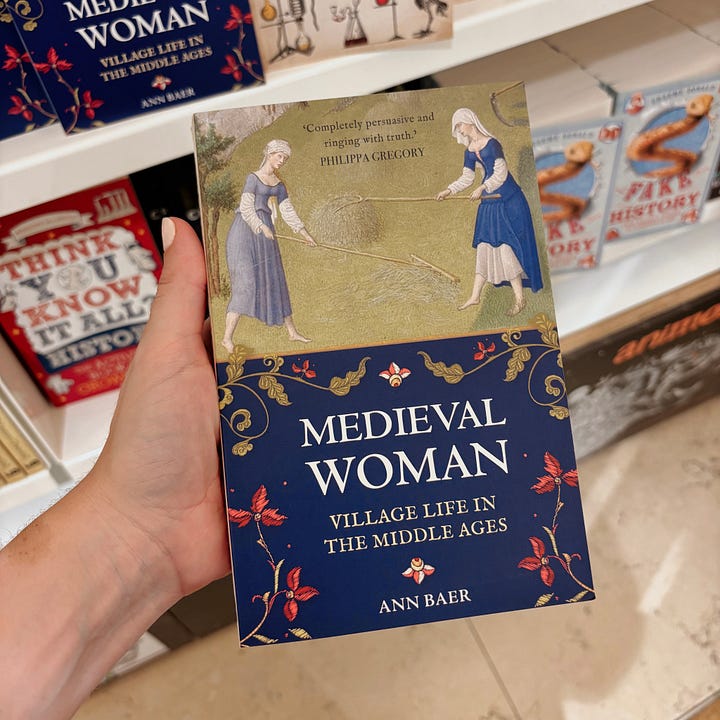

No trip to the British Museum would be complete without a quick stroll through the book shop. I didn’t purchase any because my TBR pile is already too long and I simply cannot afford all the books I want! If I was made of money, however, these are the ones I would have been tempted to buy…

So there you have it! My pilgrimage to the British Museum, my favourite historical place, for 2025 is complete.

What about you? Do you have a favourite Museum? Or a favourite artefact? What do you love so much about it?

If you enjoyed this post, you might also enjoy…

All images author’s own.

I'm not sure I have a favourite thing, there's just too many but the BM and the V&A are surely some of the most interesting and absorbing places in London. Being a buildings nerd I love the Weald and Downland Museum (or whatever it's newer name is?!).

PS I made the big hand-hewn oak sign at the main road entrance to Sutton Hoo - that too is a special place

Lovely travelogue! But I was a bit puzzled - you seem to suggest that the BM has sections which *aren’t* the medieval galleries. Who would have thought it!