Powerful stories hidden within place-names

Travel Diaries | October 2024 | Beddgelert, Wales

How much attention do you pay to place-names?

They’re all around us.

We speak them countless times each day.

And yet we probably don’t give a moment’s thought to their origins.

Place-names are, however, one of the biggest non-written sources for ancient and medieval British History.

Sarah Semple, archaeologist, says the following:

Place-names that survive within the English landscape and in surviving documents offer another potential source of information on popular [as opposed to elite] perceptions [of the past].1

In other words, place-names give us an insight into the lives of people otherwise lost to history.

Well, then, what can they tell us?

Place names can reveal individuals who were once regionally or nationally significant, for example:

Huddersfield, likely derived from the location of a field belonging to a man called Udda

Conisbrough, the site of the cyninges (king’s) burh (fort)

Wednesfield, denoting another field, this time belonging to Woden (perhaps a place dedicated to his worship?)

Place names can reveal the influence and spread of different people groups.

Have you ever noticed how the names just sound different in the north of England than they do in the south, for example?

North: Wetherby, Milnthorpe, Grimston - all betraying Norse linguistic influences

South: Guildford, Thursley, Reading - much more Anglian and Saxon in origin

Place names can also reveal pre-Christian belief systems.

Harrow, from hearg (temple)

Wensley, Woden’s lea (Woden’s grove)

Thursley, Thunor’s lea (Thunor’s grove)

Place names are one of the biggest non-written sources for ancient and medieval British History.

I’ve always been alert to place names, knowing that such treasures lie in their etymologies. And as an early Anglo-Saxon historian, place-names are a key source alongside written and archaeological evidence.

So you can bet I was curious to know the origins of ‘Beddgelert’ when I visited recently.

Beddgelert (pronounced beyth-gel-ert) is a small village in the far north east corner of Wales, nestled in the shadow of the mountains of Eryri (Snowdonia National Park) and just a stone’s throw from Yr Wyddfa (Snowdon).

It is sensationally beautiful.

More often than not, this part of Wales lies drowned, heavy rainfall combining with waterlogged earth to blur the boundaries between land and sea.

But not this time.

This time, the sun illuminated spectacular ridge-lines crowning the valley, giving life to the abundance of flora and fauna drawing on the region’s sodden ground.

We were visiting for a wedding, and as I traipsed through the village willing my toddler to sleep in his pushchair, an otherwise unremarkable sign caught my eye.

Look closely at the brown marker and you’ll see it.

Gelert’s grave, to the left.

Gelert’s grave.

Or, in Welsh, Bedd Gelert.

Presumably the Bedd Gelert after which the village earned its name.

Who was Gelert, I wondered?

What was so special about him that his burial place named a whole village and has become a tourist attraction?

One legend claims the following…

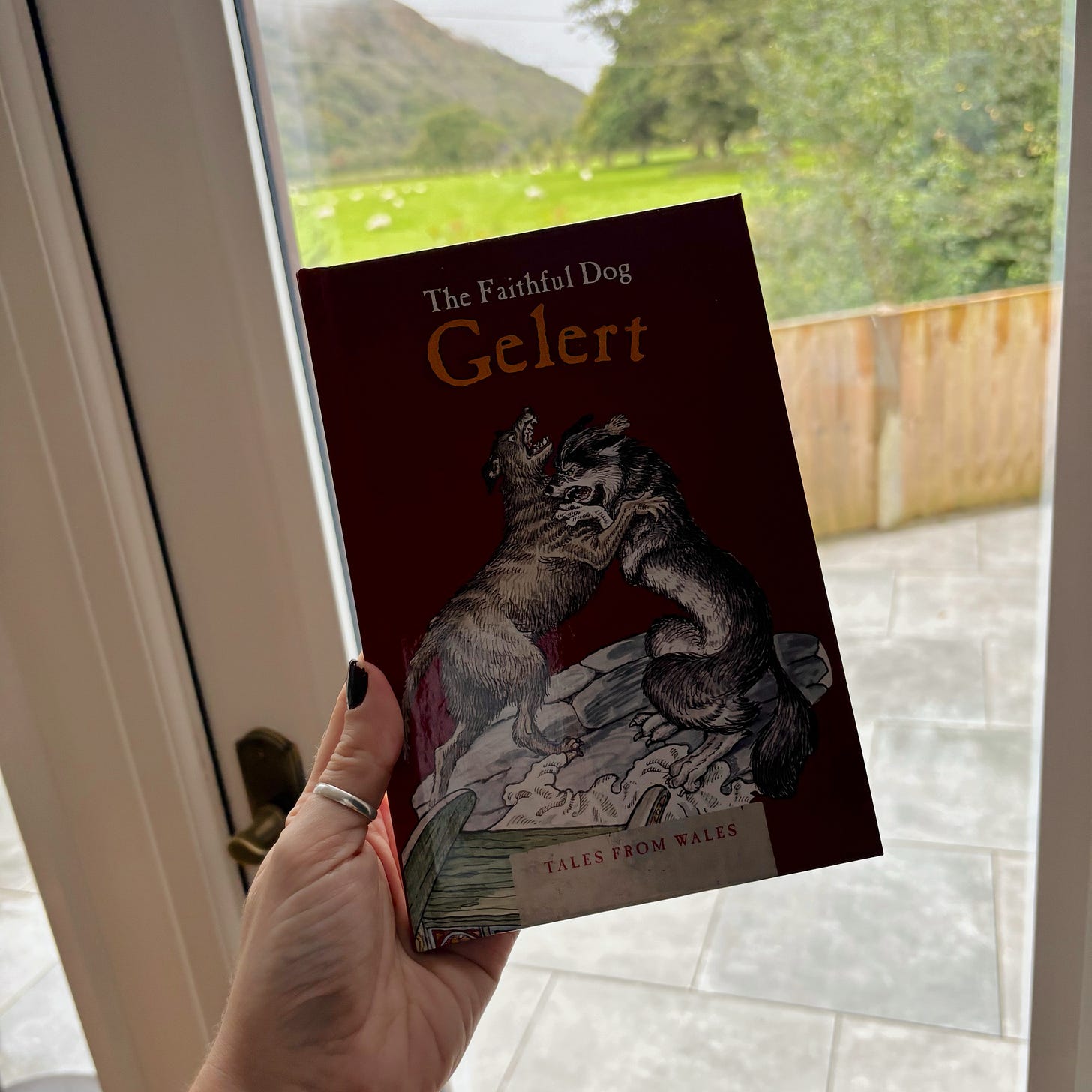

The Faithful Dog Gelert

In the legend, Llywelyn the Great returns from hunting to find his baby missing, the cradle overturned, and Gelert with a blood-smeared mouth. Believing the dog had devoured the child, Llywelyn draws his sword and kills Gelert. After the dog's dying yelp, Llywelyn hears the cries of the baby, unharmed under the cradle, along with a dead wolf which had attacked the child and been killed by Gelert. Llywelyn is overcome with remorse and buries the dog with great ceremony, (then leading to the town name) but can still hear its dying yelp. After that day, Llywelyn never smiles again.2

This, allegedly, is the Gelert for which the village is named, his grave now a popular tourist site.

Or is it?

Etymologically, Bedd Gelert as the site of the grave of someone named Gelert makes sense.

Connections between the remote Welsh village and the faithful dog, however, do not run deep. It would seem that the grave site was actually constructed in the eighteenth century by an enterprising hotel landlord to encourage tourism into this remote part of Wales.

So, who is the village named after then?

Much more interestingly for us early medieval historians, the Gelert concerned is probably the Christian missionary Celert, who settled in the village in the eighth century.

Though the surroundings are beautiful, attempting to journey to Beddgelert is treacherous enough in the twenty-first century on a fair weather day, let alone when blown about by March winds, struggling against swollen, burst streams, or wading through deep winter snow.

What drew Celert to the hills and mountains of this hostile extremity of Wales?

How different from our own vantage was the view from his cave home over a millennium ago?

Why was he able to draw pilgrims from far and wide?

All questions we will likely never know the answers to - yet are preserved in that most unassuming of place names, Beddgelert.

Previous Travel Diaries

Welcome to Telling Their Tales!

If you’re new here, I’m Holly and I’m passionate about sharing medieval history that’s about more than just kings and battles. I also am a big supporter of everything to do with serialised fiction and historical fiction, on and off Substack, with a series of ‘How-Tos’ and testimonies on these genres coming to Telling Their Tales super soon!

Connection and relatability are two of my key words here on Substack, and I can’t wait to uncover these hidden stories with you. I’m currently a PhD student (Medieval Archaeology), and I’m delighted to be here to serve and support you.

Paid membership starts from just over £4 per month, and includes access to our cosy history book club, exclusive instalments of my serialised novels, an ebook of short historical fiction stories, and the ability to pose your own questions in chat to our worldwide readership.

Ready to uncover the hidden tale of a favourite medieval person, place, or event? Join our Scriptorium membership to unlock your own research article or short story, created in collaboration with your very own ideas.

Want to connect with more History writers?

Join us over on the Society of History Writers, the only Substack community dedicated to sharing the history writing of its members to a global readership.

Sarah Semple, 2013. Perceptions of the Prehistoric in Anglo-Saxon England (Oxford University Press: Oxford), p.144

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gelert

I've always loved that story about the faithful hound, even if it is heartbreaking. And obviously, we should definitely decide to believe in it! Boo to Celert, hurrah for the hound!

I was there this year! Gorgeous place, but I am gutted it isn’t named after a dog but instead yet another Welsh saint. It’s a beautiful spot to go on retreat, that’s for sure.