Medieval gender studies is getting this wrong.

Expanding our understanding of past gender relations

Within early medieval archaeology, determining an individual’s gender can be a little too binary.

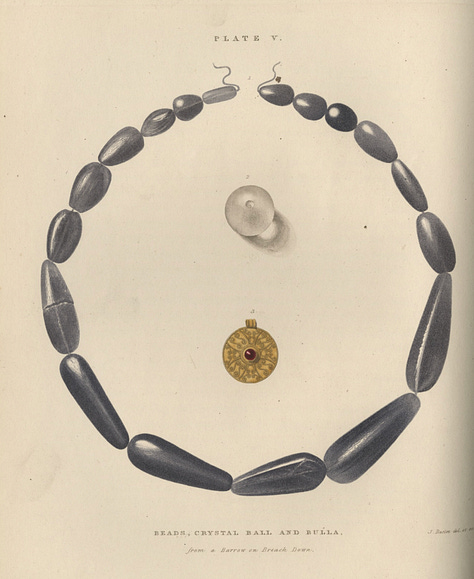

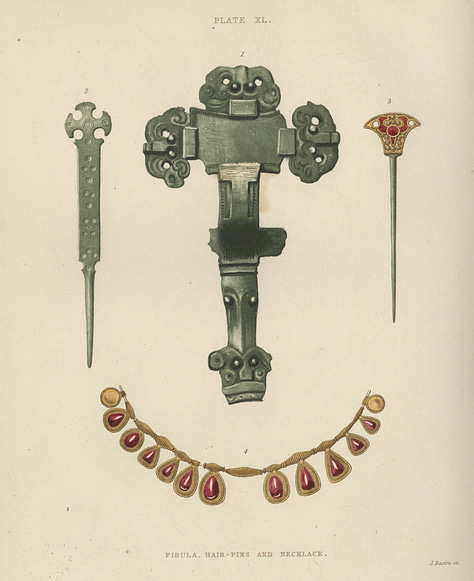

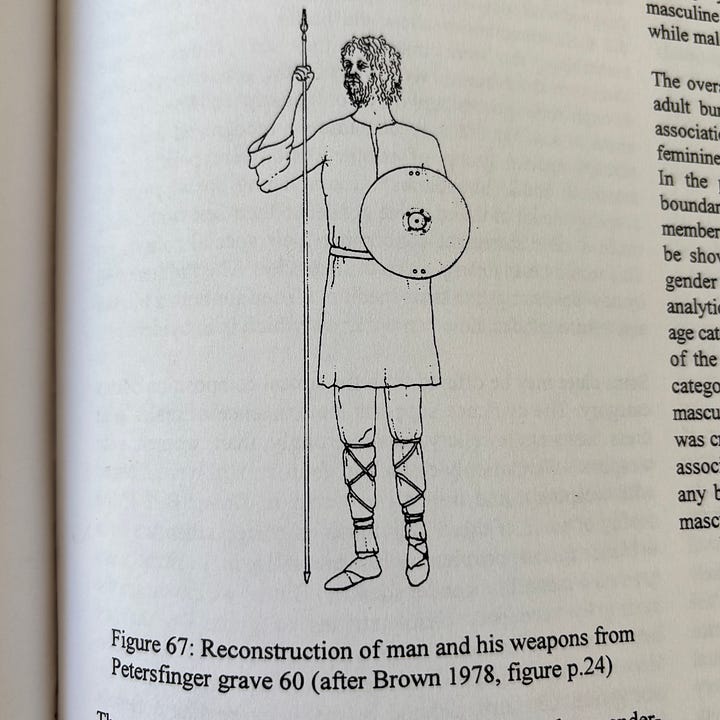

The records of Reverend Bryan Faussett (who you can read more about HERE), for example, excavating in the mid-eighteenth-century, are peppered with phrases such as ‘probably male’ and ‘certainly a female grave’, depending on whether they were buried with brooches and necklaces, or swords and spears.

By the twentieth century, this artefact-driven approach was complemented by osteological examination of the skeleton, where enough skeletal material remains to be analysed. The sciatic notch in the pelvis, muscle attachments at the base of the skull, and prominence of brow ridges on the face can, usually, give an accurate estimate of an individual’s sex.

Usually, but not always.

And the trouble comes when the artefacts don’t match the osteological assessment.

What do we do then?

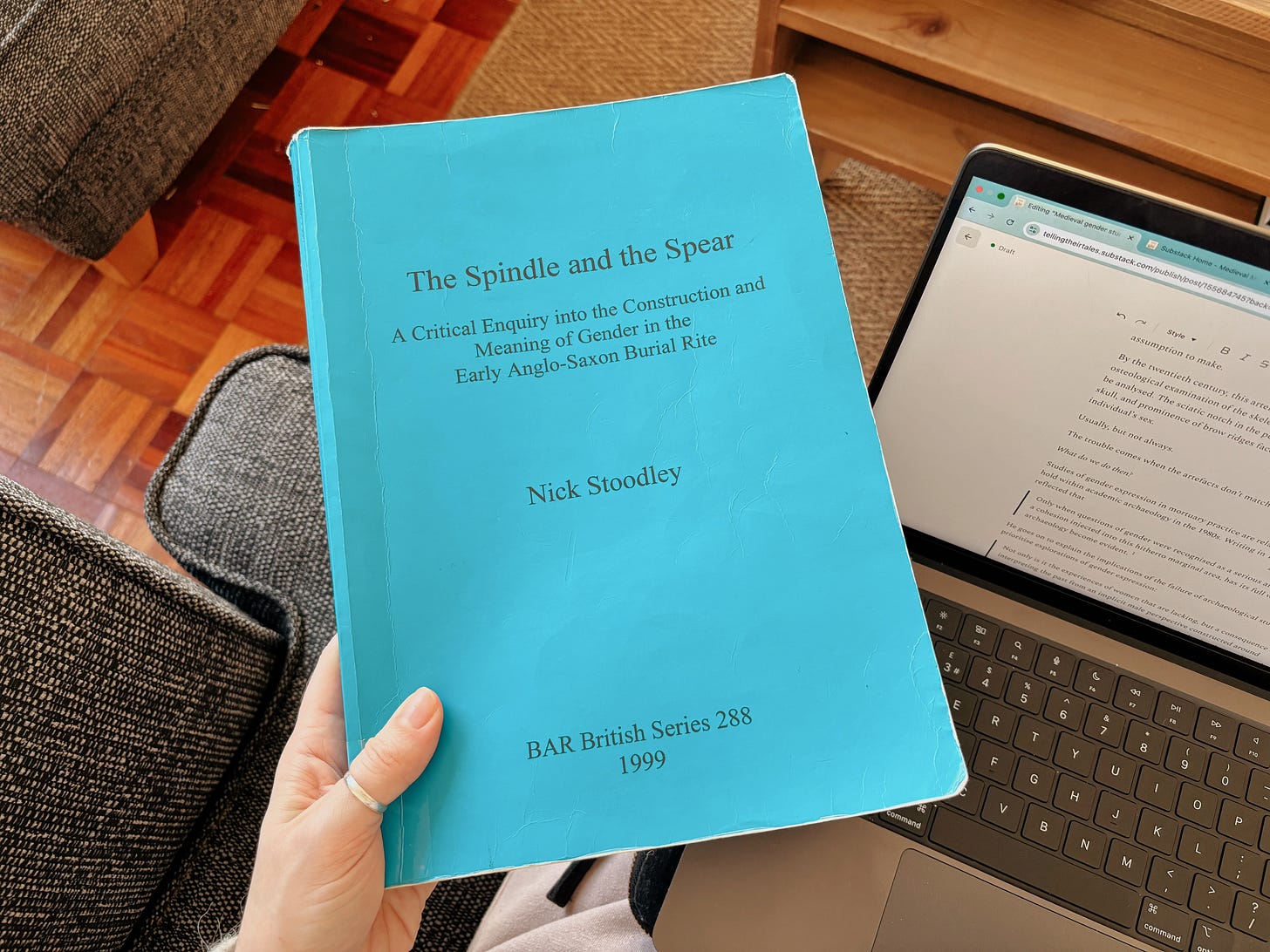

Studies of gender expression in mortuary practice are relatively new, only really taking hold within academic archaeology in the 1980s. Writing in 1999, Nick Stoodley explained the implications of the failure of archaeological studies to prioritise explorations of gender expression:

Not only is it the experiences of women that are lacking, but a consequence of interpreting the past from an implicit male perspective constructed around contemporary male experiences has also resulted in a lack of understanding about the cultural construction of masculinity … It is not enough to show women uncritically as the active force in the past, such as the tool maker, producer, creator, etc. This means that the past is written simply as before with the males replaced by females - our present understanding of the past or of gender relations does not expand.1

The problem I’ve found, though, is that in the research that follows these statements, Stoodley does the very thing he cautions his colleagues against.

Don’t hear me wrong: Stoodley’s work in this monograph is foundational to later studies of gender expression and set the tone for future research in a way that was (literally) groundbreaking.

But it doesn’t quite hit the mark for me.

Let’s dive deeper into the study.

Stoodley analysed 1636 burials, consisting of 612 males (410 probably, 202 possible), 588 females (431 probably, 157 possible), and 436 individuals whose sex was unable to be identified.2 Seeking to be ‘as rigorous as possible’, he only examined burials of individuals 18 years and over whose graves were undisturbed.3

He was able to demonstrate that

‘Biological sex is the principal source of variation underlying the decision who to place weapons and dress accessories with and by implication the template around which cultural gender was defined.’4

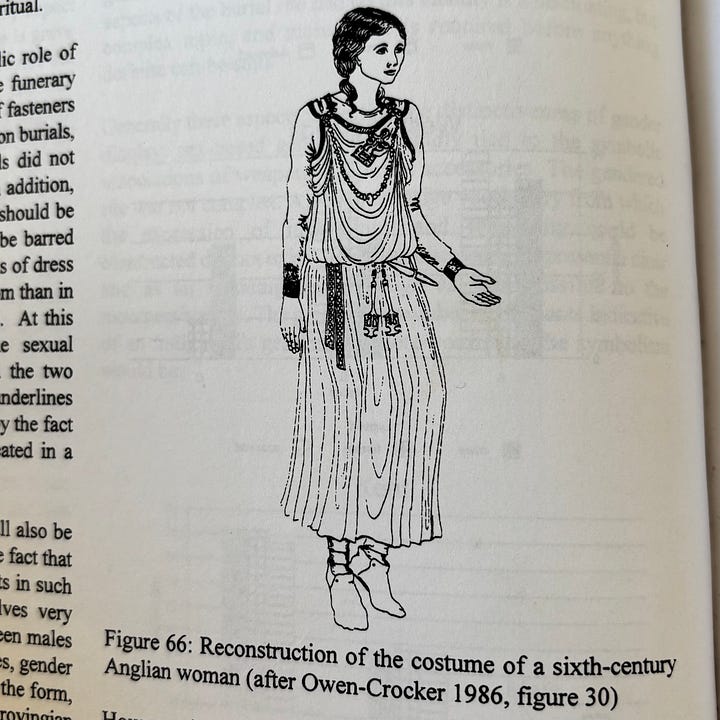

For England in the fifth and sixth centuries then, biological males were buried with weapons (largely swords and spears) and biological females were buried with dress accessories (brooches, pins, and jewellery).

He did find, however, a very small number of individuals buried with objects more usually associated with the opposite sex.

Females with swords, for example.

His conclusion?

These females must have taken on a masculine gender identity in life and so were buried as males even though they were females.

But why must a female with a sword have been wholly masculine in her gender expression?

What if, actually, our conceptions of femininity and masculinity aren’t broad enough for the early medieval period?

What if a small number of women were able to bear arms and fight alongside men as part of what it meant for them to be feminine?

Just because we associate men with swords doesn’t mean it was outside the realms of possibility for a woman to fight, even if it was outside of the expected norm.

We know that women in the earlier Iron Age and later medieval periods, particularly those at the apex of social hierarchies, took on a martial identity to lead their people in times of war.

The famous Boudicca, a popular iconic figure leading her people in revolt against the invading Romans

Catherine of Aragon marching north while pregnant

Elizabeth I delivering a rousing speech to her troops at Tilbury in the face of the Spanish Armada.

They were not necessarily any less feminine because they adopted a martial identity.

Others are talking about this on Substack, too: check out these recent posts and Notes by

and .Perhaps it is our own preconceptions about the medieval world that limit our understanding of gender expression during that time.

Stoodley’s work was an important catalyst for opening up studies on gender expression in early medieval archaeology, and much of my own PhD research owes its academic viability to his monograph.

What I hope to do in my research, however, is create space for feminine gender expression that allows divergence and the subversion of modern stereotypes. Though there was, clearly, an archaeologically-identifiable ‘norm’ for masculine and feminine gender expression, it’s those who did things a little differently that really interest me.

Bibliography

Stoodley, Nick. The Spindle and the Spear: A Critical Enquiry into the Construction and Meaning of Gender in the Early Anglo-Saxon Burial Rite. BAR British Series 288. Oxford: John and Erica Hedges, 1999.

Want to read more about early medieval gender?

Image Credits

https://www.google.com/url?sa=i&url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.britannica.com%2Fbiography%2FBoudicca&psig=AOvVaw1u50m2SGw3ASWL8t_5UhRn&ust=1737898258488000&source=images&cd=vfe&opi=89978449&ved=0CBQQjRxqFwoTCNCJydT9kIsDFQAAAAAdAAAAABAE

https://www.google.com/url?sa=i&url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.oprahdaily.com%2Fentertainment%2Fa34371642%2Fspanish-princess-battle-of-flodden-pregnant-true-story%2F&psig=AOvVaw2VEpowyjJkD3GcGoRwwOh6&ust=1737898289705000&source=images&cd=vfe&opi=89978449&ved=0CBQQjRxqFwoTCPCg7OX9kIsDFQAAAAAdAAAAABAE

https://www.google.com/url?sa=i&url=https%3A%2F%2Fartuk.org%2Fdiscover%2Fstories%2Felizabeth-is-tilbury-speech-the-birth-of-a-warrior-queen&psig=AOvVaw28qETTTJuEVD344PSxTvR5&ust=1737898321716000&source=images&cd=vfe&opi=89978449&ved=0CBQQjRxqFwoTCLD_5PL9kIsDFQAAAAAdAAAAABAE

Ibid, p.4.

Ibid, p.24.

Ibid.

Ibid, p.49.

Loved this so much! Thank you for including my Note. This was such a great read. Made me think of Georges Duby stating that the middle ages were 'resolutely male' -- like, excuse me? who made all of those people in the middle ages then? lol

Thank you for writing this and sharing this information with us!! ❤️

By his logic, let’s imagine 21st century Americans with grave goods. A man buried with an M16 would be a man, and a female U.S. soldier buried with an M16 would be … identifying as a man? That would defy the vast majority of experience even in this enlightened Year of Our Lord 2025 … how so much more in the Other Country of the Past.