Patriarchy WASN'T rife in the early middle ages.

International Women's Day X Women's History Month

We all know the age-old narrative:

The medieval world was dominated by patriarchal structures that oppressed women, systemically and systematically, across the social spectrum.

And for much of the medieval age this was true.

But for a sliver of time in the seventh century, the stars aligned to provide women unique opportunities for education, advancement, and protection from hardship, right across the social spectrum.

In honour of International Women’s Day 2025, and Women’s History Month more generally, I’d like to encourage us to challenge the existing narratives about medieval women and expand what we think we know about the past. Taking a leap of faith as I trample across some cult ‘truths’ about the medieval world, I’d like to suggest that patriarchy wasn’t rife for the whole of the middle ages, and that at times it was actually pretty good to be a woman.

Women had a powerful role in local social dynamics.

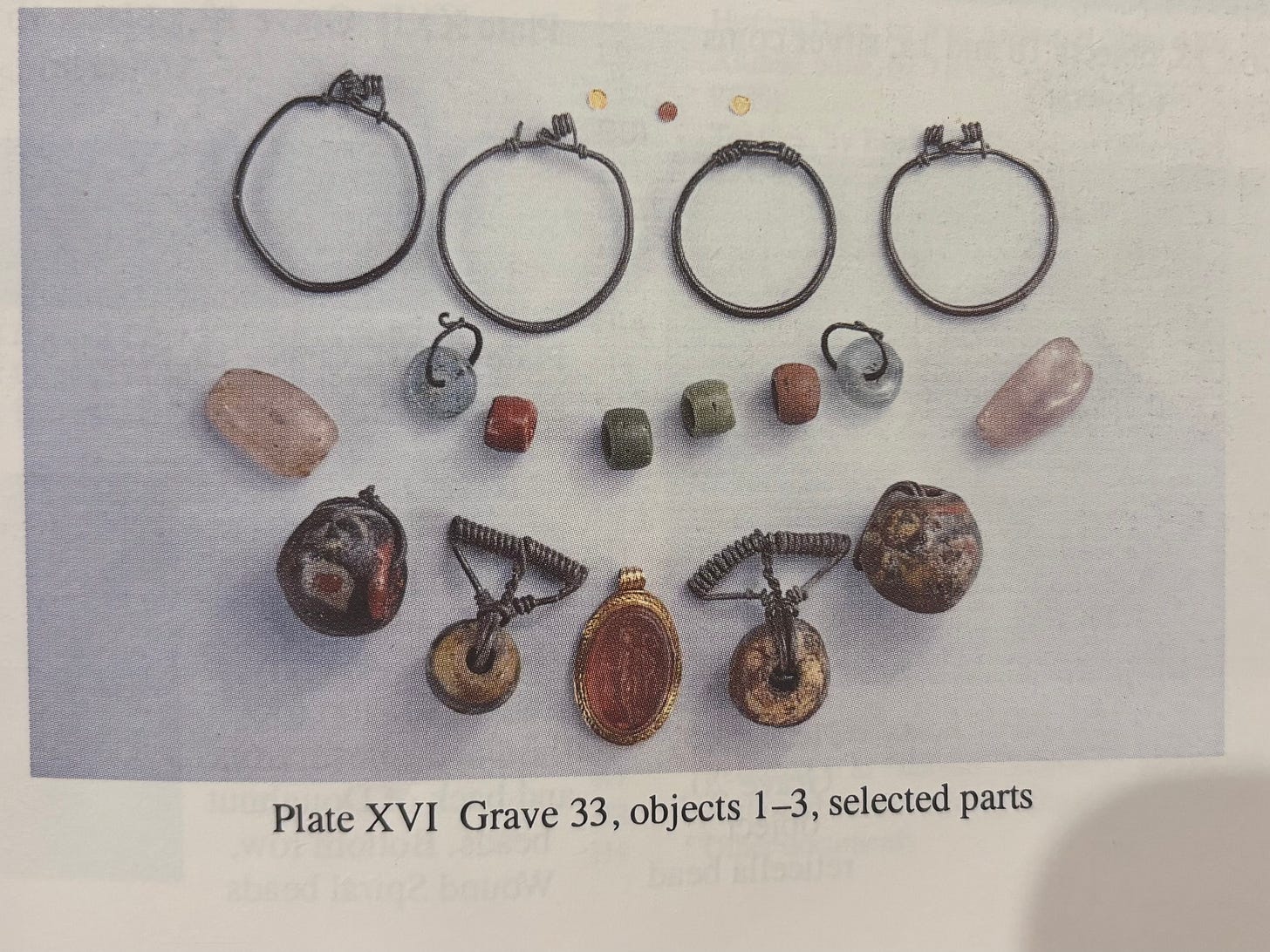

During the mid-seventh century, there is a significant increase in the use of precious metals and exotic materials (cowrie shells, amethysts, garnets) in the items deposited with women in their graves, during a period when furnished burial (the practice of burying an individual with objects) was declining, particularly amongst men. There are also particular object types buried with these women: shears, keys, relic-boxes, lockable wooden boxes.

We see these beautiful objects adorning the bodies of women who, undoubtedly, were of the highest status (princesses, early abbesses), but also those much further down the social spectrum, with women who held local, rather than national, significance.

It’s possible that political realignment to the romanized world brought changing ideas about landholding to England, and it has been argued (Hamerow 2016: 443, 444) that these lavish burials reflect the role women had in guarding their family’s earthly possessions.

From the evidence of wills, we see women across the Channel in Francia granting land alongside their husbands and on their own: Ercamberta’s will is joint with her husband Wademir, but Erminethrudis and Burgundofara needed no men to support them in their landholding (Wickham 2005).

And let’s not forget that the abbesses presiding over newly-established religious houses often received huge grants of land. Bede tells us that Ælfflæd, daughter of King Oswiu of the Northumbrians, was granted ‘twelve small estates’ on which to build monasteries, six in Bernicia and six in Deira, each of which was 10 hides (HE, III.24). We also learn that Hild was given 10 hides in Streanæshealh (Whitby) to establish her foundation (HE, III.24).

Through their ability to bear children and continue the family line, additionally, it’s possible that women were able to confer supernatural legitimacy on their family’s claims to property, becoming sacred ancestors who might intercede on the behalf of those still living. It’s worth noting here that the most lavish burials are granted to women aged 18-35, with women over the age of 45 rarely buried with wealth. Evidence in opposition to this, however, is the fact that we also see very young females being granted rich burials, suggesting that whatever status this reflects might have been inherited rather than attained in life.

Remember: males were not being buried in splendour at this time. There was something particular about being a woman in the mid-seventh century - something that we don’t quite understand yet - that meant they were adorned in life and death with lavish, wealthy items, reflecting a special status they held because they were women.

And it wasn’t just the rich women either.

The ‘upsurge’ in burial wealth for women is detectable across the social spectrum, although for more ‘ordinary’ women it tended to be singular items made of precious metals or exotic materials (Hines & Bayliss 2013).

Osteological analysis, however, has revealed that lower-status women were protected from the hardships of life: their skeletons show less evidence of heavy labour than their male counterparts (Stoodley 1999). This is not to say that their lives were easy: a disproportionate number of women died between the ages of 18 and 25, probably through the risks associated with childbearing; and their skeletons show just as much evidence for traumatic injuries such as broken bones. But it seems that the division of labour protected them from hard physical work.

There is also no indication that they were treated differentially with food at this level: their diets seem to have been pretty similar, although males had a slightly higher sugar intake, indicated by a higher incidence of caries on their teeth. The author of the study suggested that males sometimes had more access to sugary foods, which he equated with higher-status foods, but I wonder if the caries simply indicate that medieval men liked to have a pint (or more) with their mates after a hard day’s work in the fields…!

There was something particular about being a woman in the mid-seventh century - something that we don’t quite understand yet.

Then there’s the opportunities granted to women who chose the religious life.

If there’s one medieval institution almost inextricably linked with patriarchy it’s the Church - but it’s here that we see women afforded the chance to receive an education, engage with kings and bishops, and to travel.

The earliest Life of Pope Gregory the Great was written by an unknown author at Whitby during this time, indicating the high levels of literacy within these foundations.

We know from Bede that

‘numbers of people from Britain used to enter the monasteries of the Franks or Gauls to practise the monastic life; they also sent their daughters to be taught in them and to be wedded to the heavenly bridegroom. They mostly went to the monasteries at Brie, Chelles, and Andelys-sur-Seine’ (HE III.8).

Though high-status women often travelled long distances to be married, there weren’t many other opportunities to travel. Some of the women who entered Frankish monasteries loved it so much that they stayed, eventually reaching the position of abbess, while others returned to England to set up their own foundations, undoubtedly bringing an abundance of ideas with them.

And then we have the story of Abbess Hild, famous for her role in the Synod of Whitby in A.D. 664, when she arbitrated a theological dispute between a king and an archbishop. She was able to do this, however, because of her reputation for wisdom: Bede tells us that she trained multiple kings and bishops during her time as abbess.

I’d like to encourage us to challenge the existing narratives about medieval women and expand what we think we know about the past … I’d like to suggest that patriarchy wasn’t rife for the whole of the middle ages, and that at times it was actually pretty good to be a woman.

After the end of the seventh century, the tide definitely turned.

The oppression of women during the medieval period is no lie, although there were a few outliers:

Cynethryth, queen of the Mercians and wife of King Offa, who was able to have her own coin minted, a feat unique to her (thanks to

for reminding me of this wonderful woman!)Æthelflæd, lady of the Mercians and princess of the West Saxons, who ruled in her own right following her husband’s death and mounted an impressive offensive against the Vikings

But it’s not fair to say that the whole of the medieval world was marked by the oppression of women.

In fact, I hope I’ve convinced you that the seventh century was a unique blip in the narrative, a brief moment when women actually were protected and allowed to flourish.

Have I convinced you?

Is there enough evidence to suggest that the seventh century was a ‘golden age’ for women? Or was it actually just the same as the rest of the medieval age? As I am all about opening up conversations rather than providing definitive answers, I’d love to hear your thoughts on this!

My suspicion is that earlier Christianity might hold the answer as I think it provided women with new power - only to then be eroded in later centuries again when the religion became more and more linked to state politics. Is be interested to know when you think this power became more diminished and what caused that to happen. Even in later centuries we see Byzantine empresses like Zoe ruling with an iron fist and influential women like Eleanor of Aquitaine, or - going back to there religious sphere - people in Germany like Hildegard of Bingen. Something happened to change that. The splits in the church and the crusades are probably very linked to it too I suspect. I’d love to know more about how many women were translating ancient classical manuscripts - one often thinks of monks doing this but maybe this is totally wrong

I would say that yes you have convinced me! I have found it so interesting to see how the history of women is being rewritten, especially here in Norway where there has been some more focus on how some of the viking graves believed to be men are now in fact proven to be women.

great read!