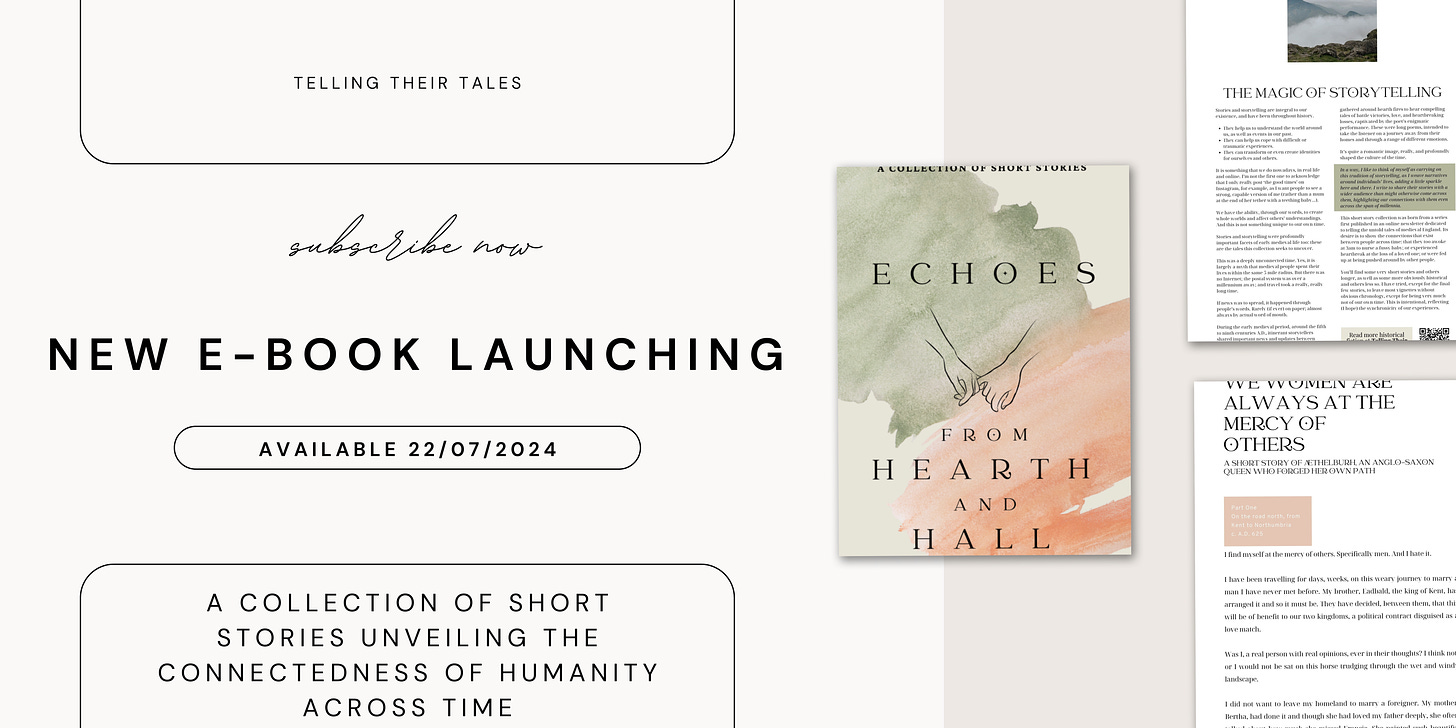

Hello, I’m Holly and I write about the untold tales of medieval lives. Subscribe for free to enjoy regular articles from me, including book reviews, historical discussions, and monthly roundups of what’s been great in the history/archaeology world. Or, even better, become a paid member to unlock ALL of my content, including all my historical fiction writing (flash fiction, short stories, miniseries and a serialised novel), to open up a world of history as you were never taught it.

Particular thanks are owed to

for her conversation about this topic on Notes recently.

Why do histories of early medieval England focus overwhelmingly on the actions of men?

Women certainly existed and acted across the realms of politics, culture, and everyday life; so what has happened to their stories? And how different would our histories be if they were restored to their rightful place?

Today we are thinking about the problem of women’s obscurity in traditional narratives of the conversion of England, during the seventh century A.D., as part of a broader conversation around the exclusion of women from early medieval sources and, as a result, later histories. You can read my most recent post, ‘Unveiling 'Dark Queens': Why Powerful Medieval Women Deserve the Spotlight in History Books’ below, in which I reviewed a recent book seeking to uncover these untold tales.

Academic history and archaeology are currently very interested in the role of women during the conversion.

It’s no surprise: gender is an extremely hot topic across most spheres of academia and wider culture. More than this, though, researchers are becoming increasingly aware that the stories we’ve told about the conversion for well over a millennium aren’t entirely accurate.

The usual narrative goes like this:

Eastern England had reverted to paganism following the departure of Roman troops around A.D. 410. There followed two centuries of darkness, with almost no evidence of Christianity. In A.D. 597, Augustine arrived from Rome under the direction of Pope Gregory the Great, armed with the Scriptures and a mission to convert these far-flung islands. Thanks to the bishop’s skilled disputation, King Æthelberht of Kent converted in the early years of the seventh century, followed by King Edwin of the Northumbrians around A.D. 625. Almost all the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms had converted by the close of the seventh century.

Much of this story is based on the account in the Ecclesiastical History of the English People written in c. A.D. 731 by a Northumbrian monk called Bede. For his time, Bede was an incredibly astute writer. We must remember that literacy had only been reintroduced to eastern England 130 years prior, equivalent roughly to the distance between 1900 and the present day. Add to this the difficulty involved in producing written texts and short average lifespans of the general population, and you find a very limited dataset from which he must have worked. His History is, therefore, remarkable, and stands up well when triangulated against other sources of information.

But Bede’s History presents a very masculine view of the Conversion of England.

It is important to say that he didn’t necessarily do this on purpose. Writing as part of the church institution that owed its existence to the evangelistic efforts of Augustine, he had to allow that mission to take the central role in his narrative. To ascribe anyone else credit would have been unthinkable. It wasn’t just the women that were left out to achieve this: Bede also denied the Irish/Scottish/British churches a major role in the conversion of England, though they certainly were significant influences.

Reading between the lines, however, it is clear that women were involved in a lot of different ways. And it’s time they were put back in their rightful places.

A major part was played by the elite women who evangelised their husbands.

MacCarron (2017) illuminates the stories of four such marriages: Æthelberht of Kent and Bertha; Edwin of the Northumbrians and Æthelburh; Peada of the Mercians and Ealhflæd; and Æthelwealh of the South Saxons and Eafe.1 She shows

that the importance of Christian queens can be detected in Bede’s Historia when attention is paid to scriptural imagery and exegetical allusions in his text. Bede’s Historia is the only early source that refers to Christian queens at pagan courts and his presentation indicates that these women fulfilled scriptural precepts such as 1 Cor. 7:14, ‘the unbelieving husband is sanctified by the believing wife’. This theological dimension reveals the unique role played by Christian queens in the conversion of their husbands and the significance of royal marriages in the acceptance of Christianity in Anglo-Saxon England.2

I’ve written before about these exogamous marriages; you can read more about them at the link below.

It is worth noting, also, that Liudhard, the first bishop resident in eastern England for more than two centuries, entered Kent in the marriage train of Bertha, while Paulinus, missionary to Northumbrians, was granted access to that kingdom by the wedding of Bertha’s daughter Æthelburh. These bishops accompanied these women only after much negotiation; might the missionary effort have been stalled, or wiped out completely, without these women’s marriages?

Though he was unable to include women explicitly, MacCarron argues convincingly that Bede used his theological knowledge to weave their importance into his narrative more subtly, in a way that learned scholars would understand. I would highly encourage you to read her article (linked in the footnotes).

Unfortunately, many later writers (medieval and modern) simply took Bede’s account at face value and perpetuated a very masculine view of conversion.

I wonder how different our conversion narratives might be if we allow Bede’s nuances to rise to the surface.

I think we’d have a story of Bertha, a lone Christian princess in a pagan kingdom, working with her bishop and the pope to evangelise her husband. Maybe he was receptive; maybe not. Either way, she would have determined to live such a godly life that Æthelberht could not help but see the light of Christ shining from her, as instructed by the Scriptures.3 She would have prepared the way for the missionaries who arrived almost twenty years after she did, Æthelberht’s heart proving softer ground than it might have been otherwise.

I think we’d have a story of their daughter emulating Bertha’s pattern, travelling far north with her own bishop to marry a pagan. Perhaps Æthelburh also talked with him over the hearth each evening, stunning him with her theological knowledge and ability to hold detailed conversation. They might have mulled over the words he shared with Paulinus and the questions that resulted, working through things together before he finally had a spiritual experience and converted to Christianity.

I think, to take it to its fullest extent, we’d have less a story of the triumph of the Roman mission and more a story of the intermingling of a variety of Christian influences, coming together in one place and time to affect fundamental change in the very fabric of elite society.

There is so much left to be understood about the role of women in the conversion of England.

It’s an important and evolving area of research because it really does have the power to transform what we know about early medieval England. These women were there and were doing important work, but the quirks of early medieval writing mean that we have to interrogate the written sources differently or turn to other sources of data to see them. My PhD will be looking specifically at the connections between holy women in Anglo-Saxon England and the nunneries of Paris, to study the impact that monasticism had on burial practice. It sounds pretty niche, but it has the potential to change what we think we know about the role of women in the conversion of England.

This has been the second post in a series exploring the exclusion of women from early medieval narratives and, as a result, later histories. I’ve linked the first post below, and make sure to keep your eyes peeled for one more post at the start of August, in which I’ll be sharing the phenomenon of female bed burials.

To receive regular articles like this, including book reviews, historical discussions, and monthly roundups of what’s been great in the history/archaeology world, please subscribe using the button below. OR, even better, join our paid membership community to unlock ALL my content, including all my historical fiction writing (flash fiction, short stories, miniseries and a serialised novel), to open up a world of history as you were never taught it.

Similar posts you might enjoy

Did you know that you can now buy my photos from my Etsy Store?

I have photos from a range of locations across the UK, available for instant digital download, including those in the gallery below. Check it out via the link below.

MacCarron, M. (2017) Royal Marriage and Conversion in Bede’s Historia Ecclesiastica Gentis Anglorum. Journal of Theological Studies, 68 (2). pp. 650-670. https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/115475/1/MacCarron%2C%20Royal%20marriage%20and%20Conversion%2C%20JTS%20accepted%20Nov2016.pdf

Ibid, p.1.

1 Peter 3:1-2.

Rewriting History: Women's Unique Influence on the Christianization of England